By Tom Ward

Special to NKyTribune

Part 24 of Our Series: “Retrospect and Vista II: Thomas More College/University. 1971-2021”

There would not have been many American college campuses that President Lyndon Baines Johnson could have visited in September 1968 without drawing a crowd of student protestors. Although it undoubtedly helped that his visit was not announced ahead of time, the nation’s 36th president must have been relieved by the warm welcome he received at TMC.

The newly christened Thomas More College would not become known as one of the national epicenters for student protests. Reading some of the official student newspapers of TMC (such as The Utopian) and of the earlier Villa Madonna College (The Spokesman) makes it clear that the students were not hiding their heads in the sand, but were well aware of the many troubling issues of the day, including the War in Vietnam, and they freely but politely expressed their opinions in these news forums.

Yet if there were not a large number of student radicals, there were still some who believed they needed to take a more vocal stance against what they thought were unenlightened or oppressive measures at their school and to do so in ways that would not always be officially sanctioned. At times, it seems they just had the urge to poke fun, especially at administration or faculty they perceived to be overbearing or pompous. Thus, even if there were no massive protests at TMC, some students participated in another phenomenon that arose during the late 1960’s – the “underground” newspaper.

The very term “underground” conjures images of revolutionary societies hiding their efforts from the secret police of a repressive government; of necessity, their publications had to be printed in secret and anonymously if they wanted to avoid imprisonment. Although being shipped off to prison was not a concern for the students who published the various papers at TMC, they probably felt that anonymity was just as essential so they would not be expelled. It is not surprising, then, that most of these papers lack any bylines or credits for the journalists who were responsible for them.

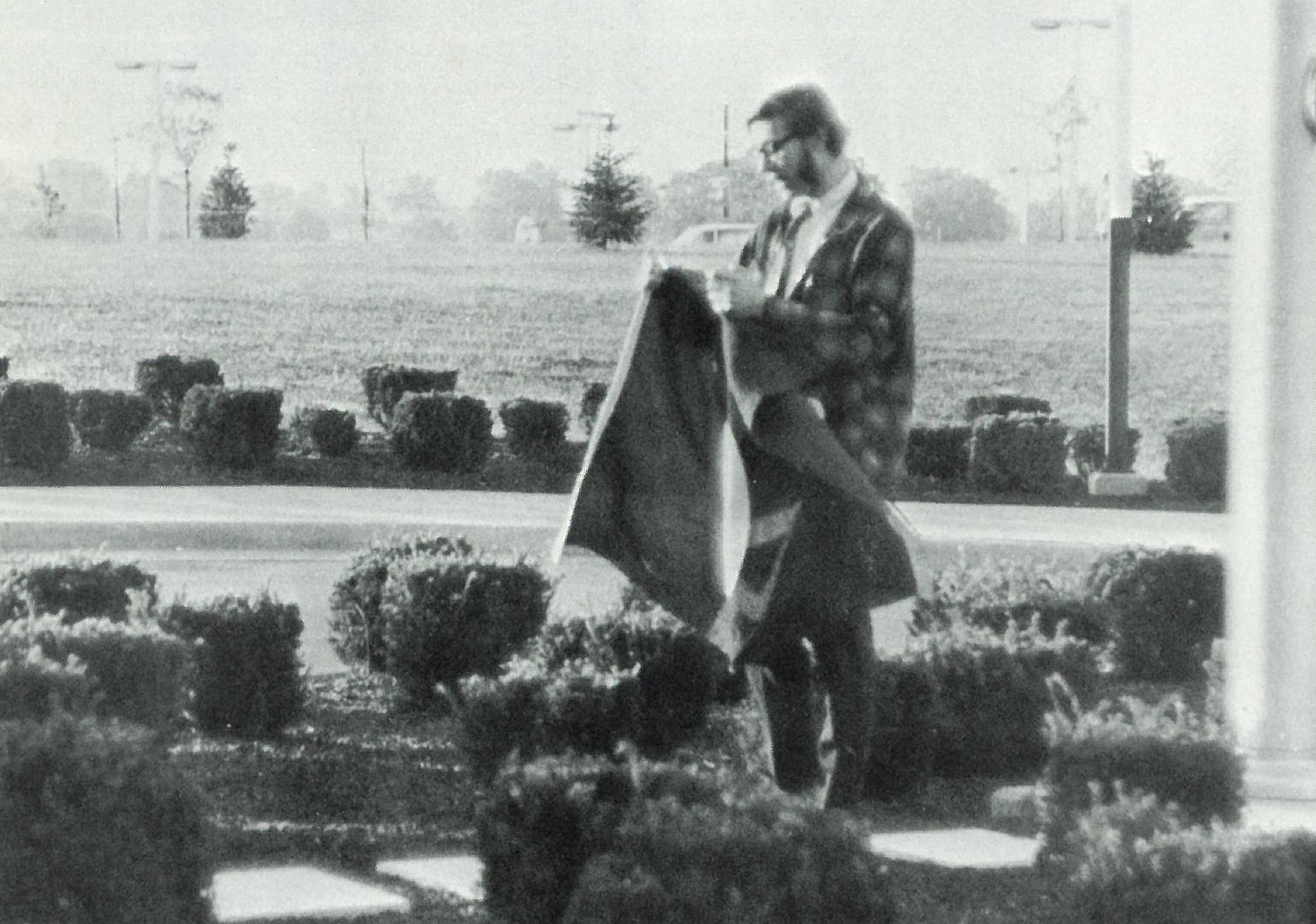

Student Frank Wermeling prepares to raise the “Peace Flag” (which did not displace the US flag) for the Anti-War Moratorium on October 15, 1969. (TMU Archives)

The names they gave to some of their underground papers reflect a sense of being in opposition to royal sovereigns of earlier times, including the era of St. Thomas More. The first underground paper (or at least the earliest of which there is a copy in the TMU Archives) was called The Royal Shaft, with Volume 1, Number 1, being dated October 1968. It was intended to be published four times per year, though there is only this one extant issue in the archives. It was written in a tone that harkened back to Merry Olde England as it criticized unjust taxation by the “House of Lords,” which was simply a parking fee for student vehicles, plus it featured an advice column written to “Dear Ann Boleyn” (second wife of Henry VIII). But more seriously, it chided the “typical” TMC student for being “an apathetic, spoon-fed babe-in-arms.” It exhorted students to “stop worrying about those damned grades” and become more involved in college life. It further tried to incite a boycott of the overpriced meals in the Commons. The Royal Shaft did not neglect national politics – it endorsed comedian Pat Paulsen for president. (Paulsen had a running skit on the Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour that year in which he declared himself a candidate for president).

The Archives contains two papers with the title Underfoot, dated fall 1969. Because they are numbered as 2 and 6, it seems there were more issues in the sequence that were not preserved, or else the editors lost count of the editions they printed out on mimeograph machines. It had as one of its stated goals to work with other students who edited The Utopian to make TMC “more of a college that really has something to offer.” Apparently, the editors saw part of that goal as questioning the requirements for Math and Science courses for non-Math/Science majors. They also espoused the admirable goal of enrolling more African-American students and were critical of what they saw as a lack of serious recruiting.

It may be enlightening to put these early papers in the historical context of what was happening on other American campuses. The year 1968 witnessed the “Days of Rage,” when radicals of the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and others went so far as to seize control of campus buildings; the protestations in the TMC papers seem quite mild in comparison. The Anti-War Moratorium on October 15, 1969 was promoted nationally, and many TMC students participated in events on their campus planned by the “Ad Hoc Committee to End the War in Vietnam”; the 1970 Triskele (TMC’s yearbook) contained photos of events, mostly involving speakers, and prefaced the section by saying “Despite predictions that it just couldn’t happen at TMC, the October 15 Moratorium did happen and did with 300 to 400 participants.” Many students also attended sponsored college-wide events on the first Earth Day held on April 22, 1970. While some might have argued that “student activism” at TMC was really more of a “lack thereof,” it is clear that students did care about what was happening in the nation and in the world.

There was a gap between those first two papers and the next one, Revelations, a gap during which pressing national issues had changed. Revelations was a longer paper consisting of several pages, of which two issues are in the Archives. These are not dated but are numbered as 1:1 and 1:3. The latter one has a note written in pencil, “c. 1974,” by the first TMC Archivist, Sr. Mary Philip Trauth, SND. Internal evidence indicates that she was likely correct.

This was the time during which the Watergate scandal dominated national headlines. “Streaking” (running nude in public) was a short-lived fad – did it have any effect on the righteous indignation raised against an art show at the college that contained some drawings of nudes? The editors of Revelations believed that President Richard DeGraff’s stated reasons for transferring the art show from the library corridor to the commons mezzanine were disingenuous – far from protecting it from vandalism, they believed that he wanted to put it where fewer people would see it. See Part 20 on Darrell Brothers for more on the nude art controversy: https://nkytribune.com/2021/11/our-rich-history-thomas-more-college-legend-artist-darrell-brothers-art-still-hangs-around-campus/

Runny Mede weighs-in on the question of faculty “no-confidence” vote regarding Dr. DeGraff, Nov. 29, 1973, page 3. (TMU Archives)

If students did not take bold stands during the 1960s, one or two did something quite daring at the time of Watergate. Although I have found no definite corroboration of the story, Sr. Mary Philip relates what she heard concerning a bust of President Richard M. Nixon that had been donated to the college by Republican state representative Carl Bamberger in 1969. According to a note Sr. Philip typed on an envelope bearing a certification card from the sculptor (Mike Makras), students took the bust that was placed somewhere along the library mezzanine and tossed it over the railing, smashing it to bits. This would have signaled their opinion of the embattled president beyond any chance of misinterpretation. (The fact that there is no bust of Nixon on campus lends credence to the story).

The longest-running paper (four issues and a supplement) was titled Runny Mede after the field in England where the Magna Carta was signed in 1215. Its stated purpose in its first issue (November 29, 1973) was to counteract the “gross gap in communications” on campus in which “the TMC community are intentionally kept in ignorance of the workings of the institution.” They also asked for “feedback and comments of the entire college community,” and the editors followed through on their commitment to print all opinions.

One concern the editors highlighted was their perception that TMC was racist. They called to task students, as well as faculty and administration, for racist comments and conditions. To them, it would have been more honest if TMC did away with “our phony liberalism and put up a huge sign at the entrance: ‘We prefer middle-class white Catholics, but we’re so broke we’ll take anybody’ ” (Runny Mede, Mar. 8, 1974).

As noted above, it was to the credit of the editors of Runny Mede that they printed letters to them that were very critical. One reader chastised them as “bitter” and “cruel” in their characterization of an administrative officer. The paper had berated his change in attitude after having been appointed to a higher position, saying he had gone from being a “rebel” to being “DeGraff’s biggest supporter,” changing his “shoddy corduroy [sic] to tacky blue pin stripes” (Runny Mede, Jan. 21, 1974). But the criticism did not seem to soften the editors’ own harsh criticisms of college personnel.

Of course, it was the nature of underground papers to be satirical and sarcastic while skewering people and policies with which they disagreed. Yet the critics of Runny Mede were correct that some of the humor was mean-spirited at times. This was not only un-Catholic, but, as one correspondent on the TMC staff pointed out, contrary “to the one thing your generation has been trying to get across to people for the past few years – ‘Love and Peace’” (Runny Mede, Feb. 4, 1974). Runny Mede could counter such arguments, however, by observing that it was seeking to be a positive force for change – “Negative means (views) may be expressed but will hopefully lead to positive action,” even though by doing this, it might offend the “Beauty-truth-love-harmony people” who seemed to want to ignore problems and avoid confrontation (Runny Mede, Jan. 21, 1974).

Was this truly the fate of the President Nixon bust? (Note typed by Sr. Mary Philip Trauth). (TMU Archives)

President DeGraff was apparently unhappy with the publication of Runny Mede. The official student paper, The Utopian, reported, “It seems that Dr. DeGraff is accusing almost everyone of publishing the Runny Mede,” while the “Student Government emphatically denies that they are the publishers…” (Utopian, Feb. 4, 1974). (The Student Government president admitted, though, that some members contributed to Runny Mede in an unofficial capacity). The unknown editors reported that Dr. DeGraff had even convinced the one financial supporter of the paper to desist, forcing the students to pay all costs themselves (Runny Mede, Feb. 4, 1974). This financial supporter, however, later informed them that he, in fact, had called Dr. DeGraff to apologize for his support of a student paper, the nature of which he had initially misunderstood (Runny Mede, Mar. 8, 1974).

One obvious question that comes to mind in reviewing these TMC “underground” papers is: who were these students? With their evident knowledge of Medieval and Renaissance times and interest in politics, it is tempting to think that they were perhaps students of the Humanities, for example, History. Their writing is, for the most part, passably grammatical, which could indicate English majors. At any rate, students in the traditional Humanities would seem the most likely to be the clandestine writers, though students in other fields undoubtedly had similar concerns.

There was one student, Kelly Marts, who attached her name to what she wrote in one issue of Runny Mede. This was, she explained in the next issue, because the duplicating service at TMC insisted that the articles had to be signed by the writer for the paper to be printed. Ms. Marts pleaded the obvious fact that it was an “underground” paper and for that reason it was not signed. But in order to meet their criteria, she consented for her name to be printed (Runny Mede, Mar. 8, 1974). Whether she or others would have continued adding their names cannot be known because this was the last issue, apart from a one-page supplement calling for Thomas More students to join together for an organized “streak-in” (As mentioned earlier, “streaking” meant running naked) (Runny Mede, Mar. 11, 1974).

The tradition of underground newspapers at TMC continued through the 1980s and 1990s, with the last one filed in the TMU Archives having been published in 2000. (One paper published in 1983 will be featured in a later part of this history regarding the administration of Dr. Thomas Coffey). But I have focused on only these earliest papers that were produced during what could be called the “Golden Age” of underground college newspapers and turbulent times on campuses in the 1960s and early 1970s. Of course, the idea of underground papers did not originate at TMC, but students here were as much a part of the times in which they lived as students all across the country. This section at least provides a sampling of the thought and wit of students who wrote about the unique situations they encountered at their own school, a school and student body about which they cared, even if they demonstrated their care by a method that seemed counter-productive to others.

Tom Ward is the Archivist of Thomas More University. He holds an MA in History from Xavier University, Cincinnati. He can be contacted at wardt@thomasmore.edu.

We want to learn more about the history of your business, church, school, or organization in our region (Cincinnati, Northern Kentucky, and along the Ohio River). If you would like to share your rich history with others, please contact the editor of “Our Rich History,” Paul A. Tenkotte, at tenkottep@nku.edu. Paul A. Tenkotte, PhD is Professor of History at Northern Kentucky University (NKU) and the author of many books and articles.