By Judy Clabes

NKyTribune editor

As the rest of the world catches the headlines — Ukrainians fight back, Ukrainians blow up key supply bridge, Russians abandon Ukrainian territory, Russians launch missiles, and more — two Northern Kentuckians are experiencing the reality every day as they pursue their humanitarian efforts in the Ukraine.

Loading supplies

Ben Dusing and John Gardner have expanded their humanitarian aid efforts in Ukraine in ways neither of them expected. Their best laid plans have given way to the plan of the minute, responding to the growing need — and to the demand for their services from the broadening community of international volunteers who have been drawn to Ukraine.

Little did Dusing and Gardner know where their willingness to serve would take them.

Dusing, who decided to live out his suspension from his law practice with service to Ukraine, was joined on his fourth trip to the region by his colleague, Gardner. They took as much aid as they could, including the bandages and medicines they were told were in great demand, purchased more in country, and rented a vehicle. While there, they have connected to a group of dedicated volunteers, made a “family” of like-minded, earnest people, found new sources of aid supplies, and are in constant demand as “sub-contractors” to an array of aid groups. As more formerly Russian-held territories of Ukraine become “liberated,” the demand for humanitarian aid has extended to remote and more dicey small villages closer to the Russian border.

As it turns out, Dusing’s facility with the Russian language (he spent a year in Russia as a youth) and the pair’s reputation for hardwork and dedication have made them a precious commodity in the volunteer world there.

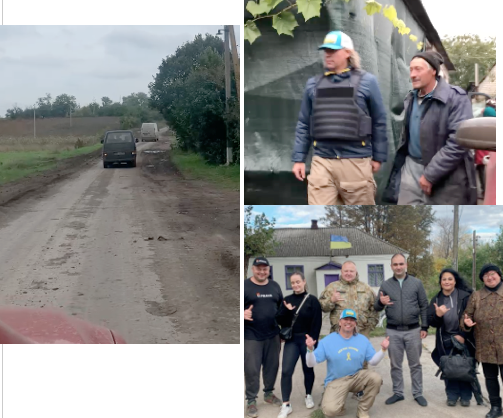

Part of the Red Cross evacuation

Most recently, they were invited to join a Red Cross-led 4-vehicle convoy to a small village that had been occupied by the Russians since March. For the first time, their mission included rescuing three “registered evacuees” as well as distributing aid. It was the first aid the villagers had seen. The village was heavily “mined,” and the rules were clear — stay only on the roads and don’t step even one foot into the grass. On the way, they saw bodies of dead Russians soldiers on the roadside. In the village, they distributed food and water and provided medical aid — and they had a strict two hours to do it. But because Dusing speaks some Russian and understands more, the villagers were eager to tell him of the attrocities the village suffered, showing him where the mass graves were, and pointing to the school where villagers were tortured.

The group could hear — and feel — missile fire in the distance and some artillery fire, but that was to be expected in the “gray zone” in which they travelled. All were wearing protective vests.

“This is surreal stuff,” said Dusing, “but overall, we are all capable of more than we think we are. I have come to love the people who are part of doing this work.”

For the villagers, he and Gardner were happy to be part of the “beginning of their liberated lives.”

“The Ukrainians are not going to stop,” said Dusing. “They are determined to take back all of their country.”

In all, the group visited two small villages and extracated five people — including a sick 90-year-old man. Two of the other evacuees, a young woman named Yulia who was going to Kharkiv to live with friends and a man Kolya who was to be reunited with this wife and 4 children, rode with Dusing and Gardner in their vehicle. Their first stop would be the Red Cross registration center in Kharkiv which is also home base for Dusing and Gardner.

Aaron, the medic, and Ben Dusing

Back in Kharkiv, a rag-tag group of volunteers gather regularly at an (unnamed) bar on the outskirts of the big city. Think of it as “Cheers,” the place where everybody knows your name. There, the owners welcome the international crowd of do-gooders and have even set aside a “Volunteer Room” for them. And there, plans are made.

Included in the group are the Canadian, Paul, who has HUGS, an NGO (Non-Government Organization) of his own and who is an experienced aid provider, and the Alaskan Dane who knows where are the supplies are and who practices his own brand of high-risk services, pushing deep into newly liberated and remote villages, and Jakob, a local ‘folk hero’ who spent months in the subways of Kharkiv to provide aid to people who were living there.

It was at the bar that Dusing and Gardner were asked to take a special mission — to deliver a medic (Aaron, from Texas) to Kramatorsk in the Donbass region, coveted by the Russians.

It turned out to be an “unreal” day that stretched into a tense overnight because of heavy, nonstop artillery and small arms fire and the closings of checkpoints along the way. Aaron was delivered safely to Kramatorsk — and Dusing and Gardner returned safely back to Kharkiv, keeping strictly to the battered roads and checking safely through the re-opened checkpoints.

Ben Dusing and a new friend in a ‘liberated village’

For a few days in Kharkiv, the pair took shelter in the lowest level of the subway along with others because of heavy Russian missile fire that hit downtown Kharkiv — and multiple other large Ukrainian cities. By then, they were used to the sound of shelling — and, like all the volunteer group, started texting their friends until everybody was accounted for.

It really is a community of volunteers, Dusing said.

For a day’s mission in Izium, the pair joined the Ordinary People Foundation to hand out supplies from the UN World Food program — boxes of food for a family for a month — to a specific list of families in a village “in the middle of nowhere.”

“These villagers are so grateful,” said Dusing, “and they love Americans. This was like ‘another day at the office’.” The group set up in a municipal center, about a kilometer from the front, surrounded by the picturesque Ukrainian countryside and handed off the aid from the back of a truck.

When the pair take off with Dane, the risktaker, they are prepared for the worst (and wearing their protective gear) — and also for the most gratifying experience — because they’ll be the first aid people in the frontline villages. They are sure to have armed security and likely to find discarded Russian uniforms, Russian sympathizers, left-behind munitions, and stashes of all kinds of supplies.

These convoys have strict rules — all in the “managed risk” category — and are required to leave so much space between vehicles and stay strictly to the bad roads and not use headlights.

On these trips, there is always the sound of artillery close by.

“The farther out we go, the more desperate the villagers are,” said Dusing. “But we have no agenda except helping people and providing humanitarian aid. Everything is harder — but the need is greater.”

They know they are going to run out of aid, even before they begin. Crowds will gather. And everybody is prepared to find shelter, just in case. And every where there are signs — “Peaceful people live here.”

These two Northern Kentuckians are living a life most people will only see in the movies. In fact, there are probably movies to be made and books to be written.

But, in the meantime, there are still many people who need help — and they mean to do everything they can to provide it.

See an earlier NKyTribune story about Dusing and Gardner in the Ukraine here.