By David E. Schroeder

Special to NKyTribune

Part 2 of our series, “Retrospect and Vista II”: Thomas More College/University, 1971-2021.

Prior to the First World War, most women religious in the United States, including Northern Kentucky, received their teacher training through an apprentice system. Experienced teaching sisters taught classes to the postulants and younger sisters on how to teach. The system worked well for generations.

However, as academic classroom work become more complicated and the range of courses more diverse, a new system became necessary. By 1914, the Jesuits at Xavier University began offering Saturday and summer sessions for women religious. About the same time, the Commonwealth of Kentucky began requiring college classroom studies for all teachers in public and private schools that wished to be accredited.

Accreditation became a serious problem. Ohio was in the North Central Accreditation Region, while Kentucky was in the Southeast Accreditation Region. At this time credits did not transfer.

Something needed to be done.

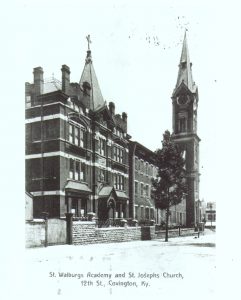

Former St. Walburg Academy on East 12th Street in Covington (in foreground) became the home of Villa Madonna College in 1929 (St. Joseph Church in background). (Courtesy of Kenton County Public Library)

The Benedictine Sisters in Covington took the first steps to organize a normal school (teaching training college) in Northern Kentucky. Mother Walburg Saelinger, O.S.B. (Order of St. Benedict) appointed Sister Mary Domitilla Thuener, O.S.B. as the first Dean of Villa Madonna College and commissioned her to develop a curriculum. Villa Madonna College opened with an enrollment of seven students on September 12, 1921, at Villa Madonna Academy in present-day Villa Hills. The college was open to the Benedictines and laywomen. At the same time, Villa Madonna College was incorporated by the Commonwealth of Kentucky.

The Sisters of Notre Dame and the Congregation of Divine Providence also began plans for their own colleges in the early 1920s. These plans changed with the arrival of a new bishop in the Diocese of Covington in 1923, Bishop Francis W. Howard. Bishop Howard had been a leader in Catholic education circles and was one of the founders of the National Catholic Education Association. After meeting with the three religious superiors, he asked the superiors of the Sisters of Notre Dame and Divine Providence to cease plans for their new colleges until he could study the situation. In the meantime, Villa Madonna College was accredited by the University of Kentucky with junior college status in 1923. Over the next few years, a four-year program was in operation.

Bishop Howard soon determined that the existence of three Catholic colleges in Northern Kentucky made little practical or financial sense. He began meeting regularly with the three mother superiors and decided that one diocesan college open to all religious orders and laywomen was the best option.

The location for the new college was the first hurdle to be overcome. It was decided that the Benedictine’s St. Walburg Academy building on East 12th Street in Covington was the most centrally located and best suited for a college program. Although the sisters mourned the loss of their decades’ old St. Walburg Academy (a high school for young ladies), they were pleased to be able to accommodate the college. College officials decided to maintain the original name and charter and the new diocesan sponsored Villa Madonna College opened in Covington in September 1929. The Rev. Michael Leick was named Dean by Bishop Howard.

Sister Irmina Saelinger, O.S.B. (Courtesy of Kenton County Public Library)

Traditionally, women religious from different orders had minimal contact with each other. They taught in separate schools and founded their own academies and other institutions. Since Villa Madonna College was now a diocesan institution, cooperation and teamwork would become essential. The sisters were also facing another dilemma, they needed more teachers with masters and doctoral degrees.

In their typical efficient way, the sisters came up with an ingenious plan. They decided to divide the academic departments and student support services (registrar and library) by religious order. In this way, each mother superior knew how many degreed sisters she would need to train for the faculty for the foreseeable future. As a result, The Sisters of St. Benedict became responsible for Ancient Languages, Mathematics, the registrar’s office and the library. The Sisters of Notre Dame took on the History and Science Departments, and the Sisters of Divine Providence led the English, Modern Languages and Education Departments. The priests of the diocese constituted the Theology and Philosophy faculty. In time, laymen and lay women were added to the faculty.

Villa Madonna College grew slowly over the years and underwent many changes. One of the consistencies for decades was Sister Mary Irmina Saelinger O.S.B. Sister Irmina taught in the Education Department and was the college registrar for decades. These titles, however, never fully described her work at VMC. She kept all the college records, arranged student housing before dorms existed, acted as the Dean’s administrative assistant and did pretty much whatever needed to be done.

Msgr. John Murphy, a future president of the college, wrote in his memoirs of Sr. Irmina, “As I stated publicly in her funeral oration which I had been invited to deliver, she should have been the president of Villa Madonna. She had the administrative and instructional experience. She was indeed the ‘walking history’ of the college. Women religious were college presidents in large numbers but in our diocese, and in others as well, they had to take second place to men, especially priests.” Msgr. Murphy continued, “I still remember with embarrassment discovering that Sr. Irmina and Sr. Celeste, her assistant, would themselves scrub the men’s and women’s lavatories at the college at night and on Saturdays. They felt it was not necessary to spend college monies, always in short supply . . . ”

In these early years, Villa Madonna remained an all-female institution. A step toward coeducation occurred in 1934 when Father Leo Streck began offering non-accredited courses to Covington Latin High School graduates. These classes were known as the Thomas More College Program and were expanded over the next decade to also include a number of accredited courses.

Msgr. Leick, Dean of the College, died on May 2, 1943. He was succeeded by Father Edmund Corby from 1943 until his death in 1944. In 1945, Covington’s new Bishop, William T. Mulloy, appointed Father Thomas A. McCarty the new Dean. Bishop Mulloy also made another important decision that year. He announced that beginning in the Fall 1945 semester, Villa Madonna College would become a coeducational institution. This move was made to accommodate the men of the diocese returning from World War II. Many of these returning veterans took advantage of the G.I. Bill and enrolled. As a result, enrollment grew and by 1946, stood at 224.

Father McCarty passed away in 1949 after only four years as Dean. His successor, Father Joseph Z. Aud, was named dean that same year and remained until 1951 when he joined the armed forces and was stationed in Korea. Despite the instability in the dean’s office, the college continued to grow. New classroom and office space was needed, as the old St. Walburg building was bursting at the seams. As a result, nearby buildings were found to meet the needs of the college. In the 1945-46 school year, two classrooms were acquired at the nearby St. Joseph Elementary School. Six additional structures were commandeered between 1946 and 1950, including private residences, an old fire station and a former saloon! These buildings were subsequently named Aquinas Hall, Thomas More Hall, Cabrini Hall, Pius Hall and Bernard Hall North and South.

Despite the primitive campus, Villa Madonna College provided a first-rate education with exceptional faculty and staff. This was recognized with accreditation status by the University of Kentucky and the Catholic University of America.

Next week: Msgr. John Murphy, a new campus, name change, the Golden Jubilee and regional accreditation.

David E. Schroeder is Director of the Kenton County Public Library. He is the author of Life Along the Ohio: A Sesquicentennial History of Ludlow, Kentucky (2014), coeditor of Gateway City: Covington, Kentucky, 1815-2015 (2015), and coauthor of Lost Northern Kentucky (2018).

We want to learn more about the history of your business, church, school, or organization in our region (Cincinnati, Northern Kentucky, and along the Ohio River). If you would like to share your rich history with others, please contact the editor of “Our Rich History,” Paul A. Tenkotte, at tenkottep@nku.edu. Paul A. Tenkotte, PhD is Professor of History at Northern Kentucky University (NKU) and the author of many books and articles.