By Vicki Prichard

Special to NKyTribune

There is a poem in R.L. Barth’s new book, Learning War: Selected Vietnam War Poems, called “De Bello,” that reads:

The troops deploy. Above, the stars

Wheel over mankind’s little wars.

If there’s a deity, it’s Mars.

Beyond the stages of combat, the varied geographies of strife – jungles, sand, and sea, where both soldiers and civilians suffer or cease – it is surely the profiteers of war who lift their arms to Mars, God of War, their prayers a national bravado that silently calculates wealth instead of body counts; a politician’s cunning wink behind a flag. The disciples of Mars are less likely to be found in a battlefield trench, a Napalmed village, or the sobs of a grieving mother.

Learning War: Selected Vietnam War Poems, Barth’s newly released book of poetry, does not glorify or rouse fist-pumping rhetoric; it’s simply the truth – the truth as Barth, who served a tour of duty in Vietnam from 1968 to 1969, experienced it, and that truth won’t sit in silence. As Barth writes in the poem, “Small Arms Fire”:

Why not adjust? Forget this? Let it be?

Because it’s truth. Because it’s history.

“I write about the war because I want to make sense of it, render it rationally understandable,” says Barth. “That’s both why I write and why I write like I write, that is, in formal verse.”

A legacy of service continues…in the jungle

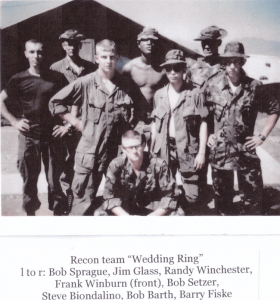

Barth, who grew up in Erlanger, traces a long line of military history in his family, and that tradition of service spurred him to enlist in the U.S. Marine Corps. An early relative of his served in the Union Army after arriving in the U.S. from Germany, and other relatives served in WWI, WWII, Korea, and Vietnam. Barth enlisted in the Marine Corps in 1966 and served through 1969. During his tour of duty in Vietnam he was an assistant patrol leader and then patrol leader in the 1st Reconnaissance Battalion.

Arriving in Vietnam in 1968, Barth recalls the smack of blistering heat and a bold stench. But there was beauty too.

“After the heat and the stench there was the beauty of the landscape – all these shades of green,” says Barth.

Barth would come to know that verdant landscape – its dense jungles and mountains – quite well.

“I was Recon, which basically meant we would take a team of eight or ten people into the jungle, the mountains, and run Recon, then run back – just a cycle,” says Barth. “As a result, I knew the jungle very well, and certainly knew what the mountains were like.”

“The Patrol,” a powerful and compelling poem that Barth says he’d tried to write for more than 40 years, speaks to the tensions of navigating around North Vietnamese patrols up in those mountains.

“I know what solved the problem,” says Barth. “I said, ‘I’m going to write this poem – no anger, bravado, sarcasm – flat a tone as I can write it in and that’s it.’ And it worked.”

An excerpt from the poem reads:

At times, patrols passed barely three feet off,

While we knelt motionless and camouflaged.

I wanted a surprise assault right there,

But that was not our mission: ours to watch,

Call in intelligence and then di-di

As quietly as possible; and yet,

As we withdrew, someone stepped on a twig.

Time stopped…The NVA began to gabble

And beat the bush, and I got on the horn

To call in air support to cover us.

As the two Phantoms dropped five hundred pounders,

The shrapnel spinning near and secondary

Explosions rocking the landscape, we moved

Through the thick undergrowth until, at last,

Emerging from the jungle, we set up

On a bare hilltop where we could observe

NVA sallies from the jungle, and

Laid out our fields of fire while radioing

For an emergency extraction mau len.

No choppers flew that evening. We dug in…

The politics of war

Barth recalls “different” wars within the time frame of the Vietnam War.

“When I went in, the war was deserving of sacrifice. That did not change when I arrived in the jungle,” says Barth. “There are different wars; ’65 isn’t like ’68. I was there from ’68 to ’69. Thirteen months. As word began to reach us of protests, draft dodgers, I think it’s fair to say, only speaking for myself, that we adopted something of an orphan’s outlook – working together to do a job we signed up to do.”

R.L. Barth (Photograph by Vanessa Barth)

The rancor over the war that was playing out back home failed to distinguish between the war and its soldiers, and there would be no hero’s welcome for those returning home from Vietnam. For many, the transition from service to civilian life wasn’t easy.

“Coming home was difficult,” says Barth. “First of all, as in my case, in the space of ten days or so, I went from Vietnam to civilian life. The country’s attitude toward the war had changed, and returning veterans were not distinguished from the war itself. Obviously, no one except other veterans understood what one had experienced. Sure, some people would say, ‘What was it like?’ but they really didn’t want to know and, besides, what could you say to them? You couldn’t begin to explain, for example, what it was like to come upon an NVA [North Vietnamese Army] training camp in the middle of the jungle with an eight-man recon team; more simply, you couldn’t really explain what it was like to carry a sixty-pound back [pack] up and down mountains in extreme heat or during the monsoon season. People had no frame of reference for such a discussion.”

A poet emerges

During his time in Vietnam, Barth wasn’t writing poetry or keeping detailed journals of his experiences. He didn’t even write many letters home. A decision to attend Northern Kentucky State College (NKSC) in Covington – what is now Northern Kentucky University in Highland Heights – would be a propitious one. At that time, in 1969, much of the school’s student body was made up of secretaries, recent high school graduates, and veterans of the G.I. Bill.

“I had the G.I. Bill and thought, ‘Why not college?’” says Barth.

The experience proved to be a richly rewarding one.

“I had outstanding professors at NKSC, who really got me interested in literature – Marge Rouse and Bill Byron. I received the first Byron Award,” says Barth.

It was there that Barth became aware of a writer whose work would greatly impact his own.

“As an undergraduate, I started writing dreadful poems – free verse pieces of dreck,” says Barth. “Junior year, I took literary criticism from Tom Zaniello. One of the textbooks was called, In Defense of Reason, by Yvor Winters. I was immediately taken.”

Struck by what Winters had to say about poetry, Barth was inspired to part ways with his own writing style and began writing formally.

“I’m reading Winters, thinking about the poetry I really like, thinking, ‘Why didn’t I see this before?’” says Barth. “I started writing the way I write now.”

Barth’s experience was evidence of a professor’s profound impact on a student.

“I owe that to Tom Zaniello,” says Barth. “Tom had been to Stanford, had taken Winters’ courses. Winters had championed a bunch of writers and had writers who were associated with him. Tom had these books in his personal library and he let me read what I wanted.”

Inspiration beyond the classroom at Stanford

After earning his undergraduate degree, Barth was selected as a Wallace Stegner Fellow in Poetry at Stanford University, where Winters, whose work had so influenced him, had taught until 1966.

“I knew there had to be some of his students teaching at Stanford,” says Barth. “I knew poets connected to him were there. But I went there and learned it was not good to mention his name.”

Winters, it seemed, had become a polarizing figure during his tenure at Stanford.

“When he thought his colleagues were idiots, he said so,” says Barth.

One might be hard pressed to find much about Barth’s experience at Stanford and, particularly, his selection as a Stegner Fellow. He says he rarely brings up the Stegner Fellowship as he finds it “pompous” to do so. Besides, some of his most meaningful experiences took place beyond the classroom.

“Most of the best stuff went on at my desk alone or at lunch with someone,” says Barth.

A particularly impactful dining companion was Helen Pinkerton, a poet and essayist, and the wife of Wesley Trimpi, who taught in Stanford’s English Department. Trimpi was an expert in English Renaissance lyric poetry and classical literature. Barth and Pinkerton lunched together and exchanged poems. It was at Stanford where he also came to know Winters’ widow, the poet and novelist, Janet Lewis. In the late 1990s, Lewis asked Barth to edit Winters’ selected poems and letters as well as her own poems. Barth was up for the task, which was a significant undertaking.

“It was a major production getting the letters – they were all over the country,” says Barth. “And Winters himself had made a big point to ask people he wrote to destroy the letters.”

The body of Winters’ correspondence included letters sent to leading names in literature, among them Marianne Moore, Louise Bogan, and Allen Tate. For Barth, the letters were further evidence of Winters’ keen wit and revealed a generous nature.

“Everybody thinks he’s a curmudgeon,” says Barth. “I always thought he had a wicked sense of humor. He had enormous generosity and that came through his letters.”

In 1999, with Barth as editor, The Selected Poems of Yvor Winters was published, followed by The Selected Poems of Janet Lewis, and The Selected Letters of Yvor Winters, in 2000.

A notable war poet

After finishing up at Stanford in 1979, Barth returned to Kentucky and established his own poetry press, but after 20 years he decided he’d spent a lot of time on other people’s poems instead of his own. Once he focused on his own work, Barth published numerous poetry collections that include, Looking for Peace (1985), A Soldier’s Time (1988), Deeply Dug In, (2003), and No Turning Back: The Battle of Dien Bien Phu (2016).

Barth says his poetry has two audiences: those who served in Vietnam, or some other combat arena, and those who haven’t served.

“I have always tried to write in such a way that the first audience would say, ‘Yes, he got that right; that’s how it was,’” says Barth. “For the second audience, I hope that, even though they can never understand to the degree that a veteran can, they can get some sense of the experience, that something can resonate on a human level.”

For Barth, poetry is a form of meditation; a way, he says, to understand given experience or situation.

“Many of my poems begin with the Ignatian meditation technique of ‘composition of place,’” says Barth.

Asked about war’s impact on literature and poetry, particularly the Vietnam War, Barth believes the Vietnam War, to some degree, damaged literature.

“There was a theory – it may still be in force, although I no longer pay attention to such things – that the Vietnam War was chaotic and irrational and, therefore, literature had to be the same,” says Barth. “In fiction, the realistic war novel (viz. James Jones) was sneered at as out of touch; novels like Tim O’Brien’s Going After Cacciato were praised popularly and academically while the realist war novel had little standing in academe, although such novels continued to be written in fairly large numbers. And yet, if you asked me to name a Vietnam War novel that would tell you what the war was like I would suggest you read James Webb’s Fields of Fire, a powerful realistic novel that would tell you just what the war was like.”

As for that war’s impact on poetry, Barth finds that almost all of the poetry coming out of the war is written in free verse, something he abandoned decades ago because of its limitations.

“For every Michael Casey’s Obscenities, which really captures the language of troops, there are reams of free verse dreck – including by poets who have big reputations as poets of the war – that do absolutely nothing for me,” says Barth. “Occasionally, some of it makes for an interesting human document, but not a poem. Most of it sounds like chopped up prose; the best of them I think of as notes for a poem that still needs to be written.”

Barth resides in Edgewood with his wife, Susan. Learning War: Selected Vietnam War Poems, is published through Broadstone Books in Frankfort.

Vicki Prichard of Ft. Mitchell writes for her blog, Backroads and Bookmarks, where this first appeared.