Part 8 of our series on the 75th anniversary of the closing stages of World War II and Part 39 of our series, “Resilience and Renaissance: Newport, Kentucky, 1795-2020.”

By Paul Tenkotte

Special to NKyTribune

On Monday, August 6, 1945, a B-29 Superfortress bomber named the Enola Gay took off from the Northern Mariana Islands in the Pacific Ocean. Piloted by then-Colonel Paul Tibbets (1915–2007), the plane’s payload was “Little Boy,” the codename for the first nuclear bomb to be used in warfare. The target was Hiroshima, Japan. Weighing almost 10,000 pounds, the nuclear weapon contained uranium-235.

Paul Warfield Tibbets, Jr. was born in Quincy, Illinois, and later moved with his parents to Hialeah, Florida in suburban Miami. His family encouraged him to become a doctor, and for a year and a half, he attended the University of Cincinnati for medical training. Staying at the home of Dr. and Mrs. A. Harry Crum at 3340 Whitfield Avenue in Cincinnati, Tibbets soon realized that he did not have a vocation for medicine. Instead, he decided to pursue his passion of aviation.

The Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park includes the Genbaku Dome (A–Bomb Dome), the remains of the old Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall, built in 1915 and destroyed in August 1945. It has been stabilized by engineers to remain a lasting symbol of the ravages of war and the importance of peace. (Photo by Paul A. Tenkotte. 1991)

On February 25, 1937, Tibbets enlisted in the armed forces at Fort Thomas Military Reservation south of Newport, Kentucky, a suburb of Cincinnati. He was accepted into the Aviation Cadet Training Program. Little did he realize then that his path would make him the instrument of one of the most important—and controversial—military missions in world history (Atom-Smashing Bomb Run Made by Former UC Medical Student Who Visited Cincinnati in July,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 8, 1945, p. 1).

At about 8:15 a.m. on August 6, 1945, the Enola Gay (named for Tibbets’ mother) dropped “Little Boy.” At an altitude slightly lower than 2,000 feet, it detonated. The resulting shock wave and fireball destroyed everything in its path. As many as 90,000 people died “immediately or shortly afterward,” and perhaps as many over the subsequent years from the effects of radiation. (Kenneth Henshall, A History of Japan: From Stone Age to Superpower. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012, p. 137).

B-29 bombers, meanwhile, dropped leaflets on the island of Kyushu warning of further imminent attacks. Three days later, at 11:02 a.m. on Thursday, August 9, 1945, a B-29 Superfortress named Bockscar dropped a plutonium bomb codenamed “Fat Man” on Nagasaki, Japan (an island of Kysushu), killing 50,000 people “immediately or shortly afterwards, and more than 30,000 in later years” (Henshall, p. 137).

For further information, see “After the Bomb: Survivors of the Atomic Blasts in Hiroshima and Nagasaki Share Their Stories,” Time.

For further information, see “General Paul Tibbets—Reflections on Hiroshima,” Voices of the Manhattan Project.

World War II was soon over. On August 15, 1945, Emperor Hirohito announced Japan’s surrender. It was the first time his voice had ever been heard on radio. On September 2nd, the Japanese signed the official documents outlining unconditional surrender aboard the USS Missouri.

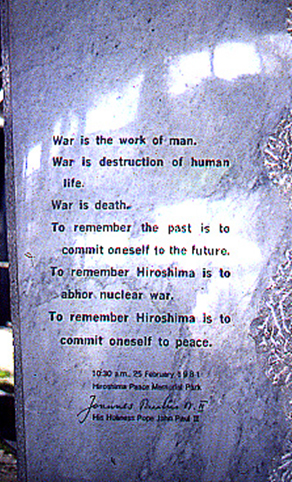

This stone at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial contains quotes from a speech delivered by Pope John Paul II on the occasion of his visit there in February 1981. Photo by Paul A. Tenkotte, 1991. For the complete transcription of Pope John Paul II’s speech at Hiroshima, see: Pope John Paul II, “Appeal for Peace at Hiroshima,” February 25, 1981. Catholic Bishops’ Conference of Japan

The US-led international Manhattan Project, which had developed the atomic bomb, employed more than 600,000 men and women. J. Robert Oppenheimer (1904–1967) was one of its leading physicists. Dr. Oppenheimer, born to Jewish-immigrant parents in New York City, had many diverse interests, including studying the Sanskrit language of India. He was fond of Hindu scriptures, and attributed the Bhagavad Gita to informing his philosophical outlook. On July 16, 1945, Oppenheimer witnessed the testing and detonation of the world’s first nuclear bomb at Trinity (the codename that he gave the testing site in New Mexico, now part of the White Sands Missile Range). According to Oppenheimer, a verse from the Bhagavad Gita entered his mind: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.”

Years later, in summer 1991, I was visiting Japan on a fellowship. One day, some colleagues and I decided to board a train to Hiroshima. As we were walking through the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park in Japan, I spotted a granite stone with an inscription. It was a quote from Pope John Paul II (1920–2005), who spoke there during a February 1981 visit ten years before: “To remember the past is to commit oneself to the future.” That quote, as well as the verse from the Bhagavad Gita, echoed clearly in my mind. The museum was a respectfully quiet space, conducive to prayer and meditation. Its focus on humanity connected visitors to a larger world.

The following summer, in 1992, I led a student tour to China. On the return trip home, we stopped in Hawaii for a “jet-lag visit” to historic sites, including Pearl Harbor. We experienced utter silence and respect as we ferried out to the USS Arizona. The Pearl Harbor National Memorial silenced my soul—and those of my students—in deep and abiding ways. Like Hiroshima, it was sacred ground, connecting all of the visitors to one another in profound reverence.

Fast forwarding to the summer of 2020, in preparation for writing this article about the 75th anniversary of the end of World War II, I first realized that Paul Tibbets had spent some time at my alma mater, the University of Cincinnati, and like me, had been interested in medicine. In addition, I had no idea that he had enlisted in the armed forces at Fort Thomas. The world seemed an even smaller place than it did before.

On Tuesday morning, August 7, 1945, the Cincinnati Enquirer introduced its readers to that smaller modern world of the atomic age. “The most terrible destructive force ever harnessed by man—atomic energy—is now being turned on the islands of Japan by United States bombers. The Japanese face a threat of utter desolation, and their capitulation may be speeded up greatly.” To deliver the same firepower as the Enola Gay’s payload, the newspaper explained, would require 2,000 Superfortress B29s carrying traditional bombs (“Atom Bomb May Force Japan to Quit; Explosive is Mightier than 2,000 B-29s,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 7, 1945, p. 1).

On a daily basis, the Cincinnati Enquirer carefully clocked the days that had passed since the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. On August 7, 1945, for instance, the newspaper’s timetable stated “1,340 Days since Pearl Harbor.” The region’s residents waited anxiously for final word of a surrender. At 6:02 p.m. on Tuesday, August 14th, President Truman announced that Japan had surrendered (August 15th in Japan because of the time difference). V-J Day (Victory over Japan) had arrived, although the official surrender would be accepted aboard the USS Missouri on September 2nd.

With President Truman’s announcement, the cities of Cincinnati, Covington, and Newport went wild with celebrations. The Kentucky Post expressed the situation best (note ellipses are original): “Kenton and Campbell county had been tense for days . . . and when it [the announcement] broke, crowds were sent into the streets of all cities . . . crowds sounding auto horns . . . crowds beating tin pans, blowing noisemakers, and giving way to anything and everything that made more noise for the merry occasion” (“Peace News Touches Off Huge Joyous Local Celebrations: Thousands Cheer Word of Victory,” Kentucky Post, August 15, 1945, p. 1).

Governor Simeon Willis of Kentucky proclaimed Wednesday and Thursday, August 15th

and 16th, as holidays. People visited local churches, such as Mrs. Emma Peters of the Latonia neighborhood of Covington, the mother of seven sons in the US armed forces. She prayed at Holy Cross Catholic Church “for peace and for the safekeeping of her sons and the sons of other mothers who are serving the cause of freedom” (“Mother of 7 Sons in Service Jubilant over Peace News,” Kentucky Post, August 15, 1945, p. 1).

Paul W. Tibbets Jr., (Photo courtest Wikimedia Commons

As long as their sons remained half a world away, however, many parents could not see beyond the victory celebrations. Around the corner, though, the future would never be the same for them or their sons. Cincinnati Enquirer journalist, Jack Ramey, accurately predicted the future: “On the threshold of peace—a peace fraught with fear that man has gone too far with the machine—stand all men.” Ramey predicted that the next contest would be between the United States and the Soviet Union: “So we know Japan’s defeat settles nothing. That the final test will be mankind’s. We know the United States never again can relax, must always be ready for anything. For we know that, just as the United States and Britain could not relax if Russia had the atomic bomb secret and they did not, so Russia or any other power great power will not relax until they have found it” (Jack Ramey, “Foreign Affairs,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 12, 1945, p. 30 news section).

Ramey stated that mankind had always somehow missed the mark, that violence had become a way of life, and that humans had never attained “abundance and fullness possible.” On both a macro and a micro scale, Ramey seemed right. On Wednesday night, August 14, 1945, Master Sergeant Sylvester Lane of 1012 York Street in Newport stepped out from his home. Lane was a 26-year veteran of the armed forces and a survivor of a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp after the fall of Bataan in the Philippines. Testifying in Newport Police Court two days later, Lane stated that he was wearing his military uniform when he left his house. “There were a group of young people in an auto in front of my home,” Lane explained, “and as I stepped to the sidewalk I was heckled and told to ‘take off the uniform the war is over.’ ” According to the Kentucky Post, Lane tried to explain “to the group that he was still in service,” but when that didn’t work, he lost his temper, attacked one of the hecklers — Robert Gadd of 407 York Street in Newport — and knocked out three of his teeth. Gadd was sentenced to 30 days in jail, fined $30, and left without three of his teeth. Decisions have consequences.

In the 1960s, American mathematician and meteorologist Edward Lorenz (1917–2008) posited the “Butterfly Effect” — namely that the fluttering of a single butterfly’s wings could eventually produce a tornado. An outgrowth of a cross-disciplinary proposition called “Chaos Theory,” the “butterfly effect” continues to excite scientists and even an occasional historian like me.

The “Butterfly Effect” offers us compelling evidence that small actions have consequences, which — over time — can build into much larger events. World War II, Hitler and Nazism, the Holocaust, Japanese imperialism and militarism, the attack on Pearl Harbor, the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, all of these and more did not happen overnight in a vacuum. They were the consequences of decades, even centuries, of actions and reactions. The decisions we make as individuals and as nations, as Jack Ramey of the Cincinnati Enquirer intimated in August 1945, are not inconsequential. And well-designed war memorials — like those at Pearl Harbor and Hiroshima — should remind us of the consequences of bad decisions. In addition, successful memorials should unite rather than divide us in the common knowledge that we all stand as humans at the precipice of our individual and collective decisions.

Parts of this article formerly appeared in chapters 3, 6, and 7 of Paul A. Tenkotte, The United States since 1865: Information Literacy and Critical Thinking. Dubuque, IA: Great River Learning, 2019.

For prior columns on our closing stages of World War II series, see:

Part 1: Veterans who landed at Normandy

Part 2: Ludlow war heroes

Part 3: Letters home

Part 4: Surviving Normandy

Part 5: Battle of Hurtgen Forest

Part 6: https://nkytribune.com/2020/05/our-rich-history-ve-day-may-8-1945-was-official-end-of-ww-ii-european-theater-victory-was-in-reach/

Part 7: Remembering Uncle Vincent

We want to learn more about the history of your business, church, school, or organization in our region (Cincinnati, Northern Kentucky, and along the Ohio River). If you would like to share your rich history with others, please contact the editor of “Our Rich History,” Paul A. Tenkotte, at tenkottep@nku.edu. Paul A. Tenkotte, PhD is Professor of History at Northern Kentucky University (NKU) and the author of many books and articles.