By Steve Preston

Special to NKyTribune

Imagine, if you will, a prominent political figure accused of treasonous actions involving foreign countries, the accusations of weaponized media using fake news, a president putting his finger on the scale of justice regarding a political opponent, and threats of impeachment. No, I’m not talking about today’s news, I’m referring to the Burr trial of 1807. And its reverberations were felt here in the Tristate region.

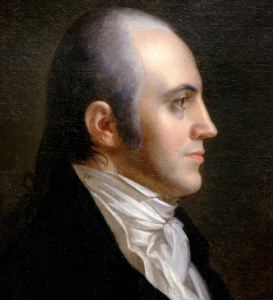

When people today think of Aaron Burr and the conspiracy that bears his name, they most likely have an image in their mind of a character who has some songs in a historically questionable Broadway show. The real Aaron Burr was just as historically questionable. What’s more, many of these “questionables” played out in Cincinnati and surrounding areas. It left a trail of wrecked lives, lost fortunes, and political embarrassment—but no songs.

Aaron Burr

The Burr Conspiracy managed to embroil the Eastern states, the Ohio Valley, the Mississippi River frontier, England, Mexico, and Spain in a cat-and-mouse game of political intrigue and possible military interventionism. The ever-changing plot was adjusted by Burr to suit him in the different situations he found himself. What Burr stated of his objectives in public often did not match what he said behind closed doors, which did not match what he told his most trusted confidantes. To this day even the most ardent Burr scholars are unsure of the breadth of his plans for the West and foreign territories. Was he planning on attacking Spanish Texas? Was he planning on overthrowing the new American government in New Orleans? Or did he hope to lead a secession of Western States to form a new empire? What is known is that Burr was taking advantage of a new nation that had several factions, leaning towards secession in the West, South, and New England.

Aaron Burr was born into a prominent family on February 6, 1756. His father was President of Princeton University, where Burr graduated summa cum laude in just three years. He served with distinction under General Benedict Arnold during the Quebec Campaign in the American Revolution. His time in the campaign helped to develop a lifelong friendship with James Wilkinson. After attaining the rank of “Lieutenant Colonel” in the Continental Army, Burr retired and returned to law school.

Upon graduation, Burr began a successful career as a lawyer, first in Albany and later in New York City, where he shared a practice with Alexander Hamilton. He soon entered politics when he was appointed Attorney General of New York in 1789. The year 1791 saw Burr being elected to the United States Senate by defeating Alexander Hamilton’s father-in-law. Most likely, this is where the bad blood began between Hamilton and Burr. Alexander Hamilton would later disparage Burr, leading to the famous 1804 duel between the two and Hamilton’s death.

Aaron Burr was the second-highest vote-getter in the very contentious presidential election of 1800. Fellow Democrat party member, Thomas Jefferson, received the highest after several rounds of voting in the House of Representatives. Burr was named Vice President.

Running mates would be a thing of future elections. Due to Burr not bowing out as a gentleman when Jefferson was the favored candidate, he was effectively frozen out by the Jefferson administration. Burr’s days were spent in the Senate chambers overseeing the day-to-day work of United States Senators. One senator became a fast friend of Burr’s, Ohio Senator John Smith, of Cincinnati.

Born in Virginia, John Smith was a man of many talents. Smith first gained prominence when he arrived in 1791 as the first Baptist minister in Columbia, east of Cincinnati. He opened a store there and was a contracted supplier to the military as well. He bought thousands of acres of land and was second only to Benjamin Stites regionally in land holdings, owning land as far away as Florida and Louisiana. He ventured into territorial politics as an Assemblyman in 1798. From there, he moved onto the national stage as Ohio’s first US Senator when it became a state in 1803. It’s said that upon arrival to Congress, Smith became a friend of President Thomas Jefferson. Unfortunately, this would not last.

Smith also enjoyed a friendship with then-Vice President Aaron Burr. With Burr as a lame-duck Vice President, Smith and Burr apparently found common interest in western lands. Both, along with Jonathan Dayton, also shared a common financial interest in the building of a canal around the Falls of the Ohio at Louisville, Kentucky. Smith seemed supportive of Burr and his seemingly innocuous plan for western conquest. Smith would provide financial backing for Burr’s expedition, as well as supplies. When Burr would visit Cincinnati on his trips West during the conspiracy period, he would often stay at Smith’s residence, going so far as to have his mail forwarded there.

Congressman Smith was not Burr’s only friend in the Tristate. General of the United States Army, James Wilkinson, was an old friend of Burr’s. They both fittingly served under Benedict Arnold during the Canadian Campaign of the American Revolution. In the last days of Burr’s time as Vice President, Burr managed to convince Jefferson to appoint Wilkinson as Governor of the newly purchased Louisiana Territory. By the way, James Wilkinson was also a paid secret agent for the Spanish. Wilkinson had been passing along intelligence to the Spanish since the 1790s. Wilkinson had warned the Spanish about the true objectives of the Lewis and Clark Corps of Discovery expedition, recommending that the Spaniards capture the group. General Wilkinson’s seat of command was located at Fort Washington in present-day downtown Cincinnati.

Cincinnati was adrift in rumors of Burr’s intentions. Charlotte Chambers, wife of Israel Ludlow, wrote in her journal of September 28, 1806, that Burr was “ . . .forming schemes inimical to the peace of his country . . . ” Newly settled General Jared Mansfield, Jefferson’s appointed surveyor-general, wrote to newspapers under the name of “Regulus,” warning of Burr’s nefarious intentions. It seems, despite his celebrity status, that Burr was not viewed favorably by all in the West.

General James Wilkinson. (Photo/Wikimedia)

In November 1806, President Thomas Jefferson finally had enough of the rumored conspiracy. He issued a proclamation, and state militias were activated to stop the conspirators from traveling down the Ohio River. Cincinnati not only called out the militia but also built gunboats in Columbia’s shipyards to pursue and intercept the rogue flotilla should it pass. Interestingly, John Smith was approached by Cincinnati leaders to help cover the cost of suppling the force. When showed Jefferson’s proclamation, Smith offered to pay up to 10,000 dollars to ensure delivery of supplies.

Cannon were even positioned, along with the militia, for extra firepower. Kentucky and Ohio militia stood ready day and night. The long, cold dark nights took their toll on the guards who soon found that blankets alone couldn’t keep them warm. Whiskey was used liberally in their warming process and to pass the time. During one of those long, cold dark nights, elements of Burr’s force quietly drifted past Cincinnati from farther upriver. The strategically placed cannons did cause some fear and concern among the inhabitants. The cannons began to thunder one day, alarming the townspeople, only to realize they were being fired as a salute at flatboats resupplying the military.

Burr and his band of alleged conspirators were eventually apprehended. At trial, Jefferson harbored so much dislike for his former Vice President that he did everything in his power to ensure that Burr be found guilty. He went so far as to issue blank pardons for use by the prosecution to tempt those who might have damaging testimony on Burr. Newspapers in the East printed stories of Burr’s apparent guilt, inducing one of his lawyers to declare that the papers were full of false reporting, or in today’s language, fake news. In the end, Burr was found not guilty. He spent the remainder of his life rebuilding his career as a lawyer and dodging creditors.

Despite his generosity to the city during the crisis and dismissal of all charges, John Smith’s life was left in tatters. Because of his friendship with Burr and his steadfast refusal to cooperate with authorities, there were calls for his removal from the Senate. A vote for expulsion fell only one vote short of passing. Smith resigned anyway. The Federal Government refused to pay him for goods and services rendered as a military contractor, and all his assets were seized to pay debts. Penniless, he moved out of the reach of American law in Spanish West Florida and returned to preaching. He died in 1824.

General James Wilkinson escaped any formal justice, as you might expect of a scoundrel of this magnitude. He continued as Spanish Agent 13. He also continued as a general, serving in a third presidential administration. Suspicion of treason would follow him all his career yet was never proven. The end to his career finally came after two crushing defeats at the hands of smaller forces during the War of 1812. He managed to lose his last battle, despite having 4,000 American soldiers fight only 400 British. Surviving his third court-martial and fourth congressional investigation, Wilkinson was summarily dismissed from leading troops and later the army itself. He would die in Mexico City, 1824, pursuing another scheme for land.

Steve Preston is the Education Director and a Curator of History at Heritage Village Museum. He received his MA in Public History from Northern Kentucky University.