By Paul A. Tenkotte

Special to NKyTribune

The Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park in Japan is one of the world’s sacred spaces. Years ago, as I was walking through its gardens, a granite stone with an inscription caught my attention. It featured a quote from a 1981 visit by Pope John Paul II (1920–2005): “To remember the past is to commit oneself to the future.”

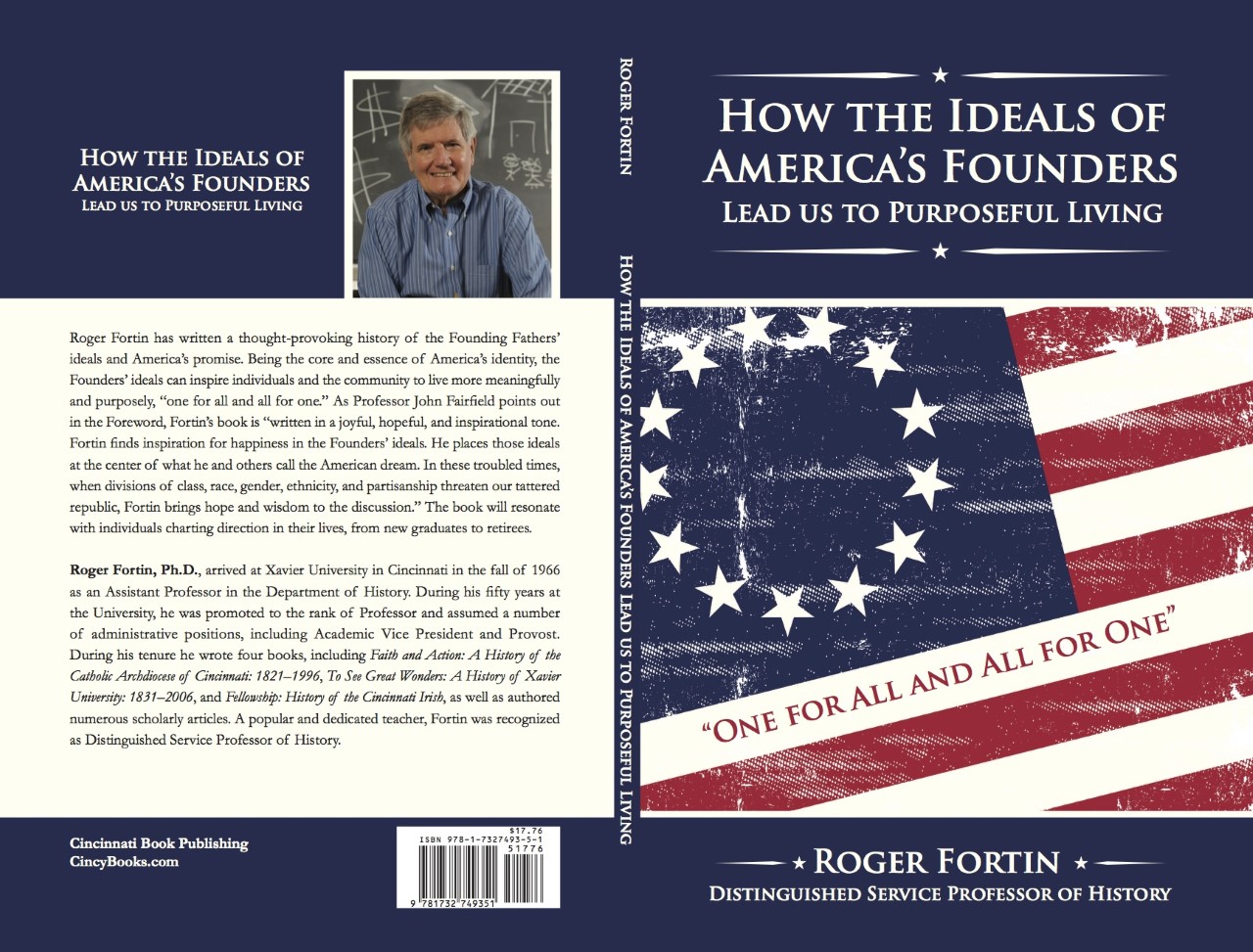

Roger Fortin, an emeritus professor of History at Xavier University (XU) in Cincinnati, has written a short yet powerful book entitled How the Ideals of America’s Founders Lead Us to Purposeful Living (Cincinnati Book Publishing, 2019).

Dr. Fortin’s prior books have helped to detail the history of our region, including Faith and Action: A History of the Catholic Archdiocese of Cincinnati, 1821–1996 (2002), To See Great Wonders: A History of Xavier University, 1831–2006 (2006), and Fellowship: History of the Cincinnati Irish (2018). Fortin also served as a longtime dedicated administrator at XU.

Fortin’s latest book is a thoughtful reflection of both his teaching and of his interaction with decades of students. As Fortin himself so eloquently states: “This book affords me the opportunity to elaborate on themes and thoughts that students and I studied and discussed, especially the Founding Fathers’ ideals that are central to America’s mission and quality of life. Overall, I’ve learned that while many of my students hoped to secure a meaningful and rewarding career, they also were very much interested in being men and women for others and living a purposeful and fulfilling life” (p. 2).

Metaphors of the founders of the United States focused on it being a new stage, a “city on a hill,” or as James Madison mused, “the workshop of liberty” (p. 6).

However, the founders also were pragmatic, knowing that greed for power and wealth would constantly assail the democratic ideals of the nation. So, they devised a system of checks and balances, as well as of separation of powers, hoping to steer the course of the new nation in the direction of progress and of fulfillment of the ideals that it espoused.

Civic virtue was necessary if America was to fulfill its high ideals. Citizens had to respect the common good of everyone, not merely their own selfish interests. The founders valued education, whose purpose was partly to instill a sense of civic virtue.

Of course, the founders — like us — were not perfect either. As Fortin concedes: “Early American leaders were a mirror of their culture. At the time of the Declaration of Independence enslaved Americans, women, and Native Americans were not viewed as equals to white men. The Founders were composed of that same mesh of good and evil that people are generally made of. During the nineteenth century, millions of Native Americans were removed from their land, slaves from Africa continued to be imported and bred, and women were legally subordinated to men” (p. 11).

The story of America, of course, is an unfinished one. We constantly strive for realization of our original founding ideals. Fortin notes well that “Over time women, blacks, and minorities achieved rights incrementally. For example, blacks, women, and gays at the end of World War II were less confident about attaining their dreams than many of their descendants over half a century later. The struggles over civil rights, women’s rights, and gay rights testify to the timeless value of our nation’s ideals as they relate to individual rights” (p. 13),

Fortin also examines the origins of the term, “American Dream.” He traces how the dream has been reinvented over the years, meaning different things to different people. Within its scope, however, the American dream has generally assumed that given a fair playing field, guided by reasonable rules, individual Americans can seek those measures that best fulfill them. To reach fulfillment, the American dream must be achievable. As Fortin argues, “There is a direct relationship between the number of individuals who pursue their goals and the health of society. The greater the number of people who can pursue their dream, the healthier is society. The smaller the number, the less healthy is the community.” (p. 20).

Like many of us, Fortin is also concerned about current threats to American democracy, which he sees as consisting of “the deliberate manufacturing of lies, debunking of the free press and long-standing government institutions, corrosion of the rule of law, and racial and ethnic divisiveness” (p. 39). The importance of the freedom of the press remains paramount to our republic, for as Jefferson wrote, “‘Were it left to me to decide whether we should have a government without newspapers, or newspapers without a government, I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter’” (p. 40).

Fortin notes well that Americans have always demonstrated a “future-oriented pattern of social redemption” (p. 22). Our democratic-republic, with all of its dreams and aspirations, is the bequest of preceding generations to us. How we receive it, guard it against threats, and nurture it is up to us. The present —and the future — do matter.

As I discovered in that peaceful garden at Hiroshima, Pope John Paul II was correct: “To remember the past is to commit oneself to the future.”

We want to learn more about the history of your business, church, school, or organization in our region (Cincinnati, Northern Kentucky, and along the Ohio River). If you would like to share your rich history with others, please contact the editor of “Our Rich History,” Paul A. Tenkotte, at tenkottep@nku.edu. Paul A. Tenkotte, PhD is Professor of History at Northern Kentucky University (NKU) and the author of many books and articles.