By Stephen Enzweiler

Special to the NKyTribune

Fifty years ago, on July 16, 1969, the greatest adventure in the history of life on earth got underway. Amid the swirling distractions of the Cold War, Vietnam, and assassinations, three men climbed into a tiny spacecraft perched atop a massive rocket and departed earth on a column of fire, bound for the moon.

Apollo 11 liftoff on July 16, 1969, carrying Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins to the moon. Courtesy of NASA.

The launch of Apollo 11 was witnessed by 26 million people in the United States alone and countless millions in 33 other countries around the world. The landing and moonwalk four days later was watched by the largest television audience in history, and it completely transformed how people all over the world viewed themselves and our species.

We were just 12 then, my school friends and I, just boys in an America obsessed with space and chasing the moon. We were impassioned sixth graders, who had been following the space program since before we could remember. By 1968, landing and walking on the moon had become the grand obsession of our lives, and we were drawn to its adventurous allure like moths unto flame. We read and collected everything we could find about the subject, learned about rocketry, spent afternoons shooting Estes rockets into the stratosphere with small creatures in the nosecones, and we stayed up all night on many a sleepover diligently mapping the moon’s craters through my brother’s 6-inch Newtonian telescope.

When Armstrong and Aldrin walked on the moon July 20th, it became a whole new ball game for us. For me, I was profoundly affected by the ghostly images on the television set showing Neil and Buzz actually walking on the moon. Possessed by a need to connect with the event, I walked outside and looked up at the illuminated crescent in the night sky, and I understood that our species was no longer confined to this world. I have to imagine every boy my age who saw the same images I saw had the same feeling. I fell asleep about halfway through the moonwalk, but managed to snap a photograph of it to remind myself in the morning that it had all been real. From that day on, I wanted to be Neil Armstrong.

Everyone in our group wanted to be Neil Armstrong, and we wanted to go to the moon. So, we called ourselves “moon men.”

Neil Alden Armstrong, first man to set foot on the moon. Courtesy of NASA.

In the weeks following Apollo 11’s splashdown, we moon men were convinced we were the future of space exploration and devoured everything we could find about the subject. We researched spacecraft, Lunar Modules, moon suits, astronauts, flight plans, launch data, rocket and spacecraft specifications, studied orbital mechanics and planetary science. Our 12-year-old minds asked questions like: What was moon dust made of? How do we simulate it at home? We greedily tried to outdo one another by speaking in astronaut jargon, using words like RCS (Reaction Control System) and TLI (Trans Lunar Insertion). My mother even got into the act by creating the term TDTI (Trans Dinner Table Insertion) when she felt it was time for me to come in and eat.

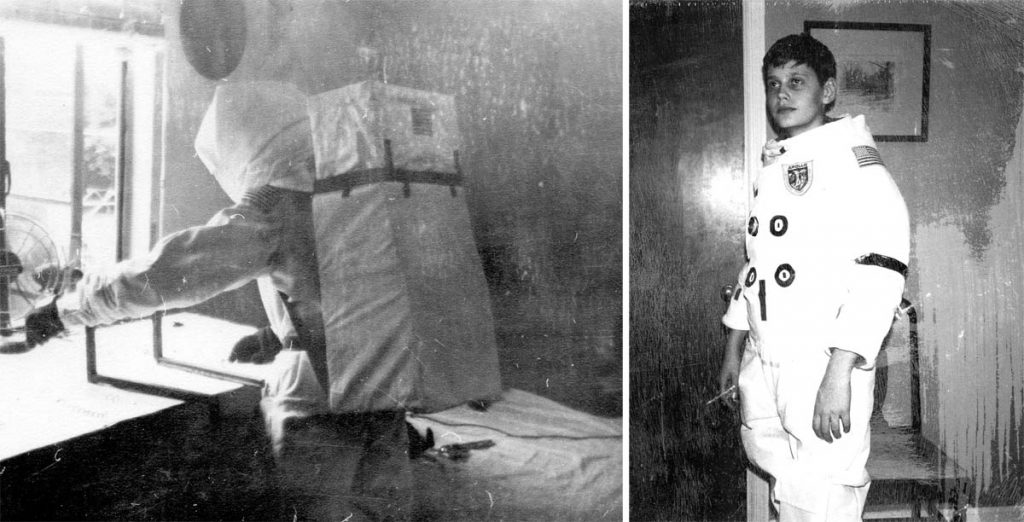

Some of us moon men went a little overboard. My best friend Terry and I actually engineered our own moon suits and equipment. My mother did the sewing and even helped us make some of the gear, including a functioning backpack with fans and tubing that provided airflow to the enclosed helmet (to prevent her baby boy from suffocating himself.) The helmet was a chicken wire and paper maché masterpiece with a locking ring and plastic faceplate. We even recreated the many scientific experiments that Neil and Buzz deployed on the moon, made possible by my father’s woodpile, collections of empty coffee cans, rolls of wire and tape, nails, paper, a myriad of cardboard boxes, and the unsolicited donation of my mother’s complete supply of aluminum foil from the kitchen pantry.

Late that summer, we had everything made and ready to go. Terry and I suited up and began our first “moonwalk” on a warm August night in my back yard, climbing down my father’s extension ladder that leaned against the house to the lunar surface for that first, historic step. We had made checklists patterned after the real ones, leg pockets for lunar samples, tools to collect imagined lunar dust, and a Westinghouse television camera made from a shoe box and a Campbell’s soup can. It didn’t work, but it sure looked real.

Of course, all of it was in youthful worship of Neil’s and Buzz’s accomplishment, but even at our tender age, we understood that ours was a gesture in praise of human ingenuity and the tenacity of man’s spirit to explore beyond the boundaries of his world. Early humans left the Great Rift Valley in Africa 200,000 years ago and we haven’t stopped exploring since. Their great migration has populated the entire earth. Others ultimately followed – Columbus, Magellan, Erikson, Shackelton, Perry, Yeager… the list goes on and on. They understood that humans must always explore what’s beyond them, or risk becoming a dangerously stagnant species headed toward extinction.

Armstrong at the moment he pressed his boot into the lunar soil at the Sea of Tranquility – 10:56 PM (EST) July 20, 1969. Courtesy of NASA.

More moonwalks followed as the summer of ’69 turned into autumn and winter. We especially enjoyed moonwalks on snowy nights, when we could see our own footprints in what we imagined was lunar dust. There were nights as we lumbered along the lunar surface when we found ourselves suddenly caught in Mr. Quallen’s headlights as he pulled into his drive coming home from work. He would always stop, stare for a bit, wave at us with a big grin, then go to bed. Some of the neighbors who saw the ghostly goings-on peered over the fence, sometimes waving, but mostly just staring in disbelief. Neighborhood cats occasionally strolled by to see the going’s on, along with an occasional raccoon and neighbor’s dog.

But if I was lucky, I would glimpse my own father, who always got up at 1 a.m. each night for a cigarette, standing in the dining room window, the cigarette’s tiny, burning glow all that gave his presence away. I can only imagine what he must have thought the next morning, to awaken and discover his backyard littered with lunar science experiments.

Terry and I would continue exploring the lunar surface in my backyard off-and-on for the next two years. But those days – those happy days of the summer of Apollo, when we basked in the sunlit hopes and dreams of the glorious missions to the moon, were soon coming to an end. The last moon landing was Apollo 17, flown in December 1972. The remaining missions were canceled. For the moon men, the end had come, too. The vast collections of news and magazine articles, all the memorabilia, models and artifacts would vanish into closets and drawers, not to be seen again for nearly half a century. The moon men eventually went their own ways as well.

That might have been the end of the story, except for a chance encounter on a cold April day in 1977. At the time, I was working as an airport lineman for Maier Aviation at Lunken Airport in Cincinnati. It was a frigid day and I had just finished refueling an airplane on the ramp when a sleek business jet landed and stopped in front of the terminal building. It discharged a single passenger: a man in a beige overcoat. The jet closed its door and quickly departed. I was inside the building doorway trying to get warm when the man walked past me, and a face I instantly recognized looked up, said a polite “hello,” then disappeared inside.

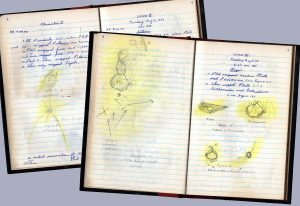

Original backyard astronomical journals kept by the moon men in 1969, recording detailed nighttime telescope observations of the moon and planets. Note the detailed mapping of the craters on the lunar surface. (Provided)

It was Neil Armstrong.

In the coming weeks and months, I would occasionally see him again, each time arriving at Lunken in the same way, and each time greeting me with a smile and “hello.” I always found him inside the terminal building, standing by himself at the front doors, waiting patiently, as he told me once, for a friend to pick him up. I quickly realized the time he waited there was an opportunity for me to approach him and perhaps chat. What does one say to the first man on the moon? Here was the original moon man standing in front of me, I thought. Here was the Korean fighter ace, the X-15 test pilot and cool head who saved Gemini 8 from disaster, the NASA astronaut and first man on the moon. Here was the ghostly figure I watched as a twelve-year-old on an old black-and-white television set. Here was the presence I had sensed that night in that sliver of a crescent moon.

I knew Armstrong had been hounded for years by the press, media, and autograph-seekers, and that he hated publicity. So, I tried to think of him as just another pilot floating around the airport property. It wasn’t easy.

Rare photos of two moon men in 1969 dressed in their homemade moon suits. At left, one simulates descending to the moon’s surface in the lunar module. At right, another poses for the camera wearing his best “to the moon and beyond” expression. (Provided)

Yet he always seemed willing to make small talk as he waited for his ride. On the third or fourth time he came, he readily remembered me. I always greeted him as “Mr. Armstrong” and I found him as approachable and polite and ordinary as if he had never been to the moon at all.

Remarkably, in all our conversations by those front doors, we never talked about NASA or the moon landing. He did, however, particularly enjoy talking about airplanes, the ordinary subject of pilots and like-minded folks. When I told him I was taking flying lessons and attending college in hopes of making a career in aviation, he was very encouraging, asked questions and offered suggestions. I considered asking his advice about becoming an astronaut, but I bit my tongue. Just then his ride pulled up outside, he said a friendly goodbye, and he was gone. I never had the chance to talk with him again.

Each generation has its heroes who teach the rest of us where we are going. For my father’s generation, it had been Charles Lindbergh who pointed the way to a world’s future in aviation. For our generation of the 1960’s, it had been the astronauts; they taught us that the destiny of man was headed for the stars. Years later, after I was well established in my own career flying with the Air Force, my thoughts occasionally returned to those summertime memories of the moon men and those brief, sunlit days at Lunken Airport spent in the company of Neil Armstrong. They are days for which I have been forever grateful, appreciative that for at least a little while, I was privileged to spend time with the original moon man himself.

Stephen Enzweiler is a writer, author, historian, and a frequent contributor to this column.

The lobby of the Lunken Airport Terminal, where Armstrong used to wait to be picked up after returning by private jet from Detroit, where he was doing some consulting with the Chrysler Corporation. (Provided)

Thanks for this informative well written article. The moon landing was a pivotal moment in US history and a reminder of what Americans can accomplish