By Stephen Enzweiler

Special to the NKyTribune

On a warm summer afternoon in the late 1880s, a little girl walked up to the front door of the residence of the Bishop of Covington and rang the bell. When the housekeeper answered, the little girl asked to see the bishop. The housekeeper showed her into a quiet front parlor and asked her to wait there. After a while, she returned and showed the little visitor into the presence of the Bishop himself – the Right Rev. Camillus Paul Maes.

Bishop Camillus P. Maes. Courtesy of Paul A. Tenkotte.

What brought the child to see Maes that day were the many public appeals he had been making to raise funds for construction on a new cathedral for the people of Covington. For more than a decade, efforts to raise money for this new house of God had been unsuccessful. The cathedral at that time, a simple Gothic Revival edifice located on Eighth Street and finished in 1854, had become too small for the growing population.

Additionally, lingering debt and a lack of funds for its ongoing maintenance left the building in a progressive state of deterioration, with a badly water-damaged roof and ceiling, inadequate gutter system, and an exterior façade that was falling to ruin.

Standing before the little girl, Camillus Paul Maes must have been a striking figure. Accounts of the time describe him as being “tall, finely built, of florid complexion and with black curling hair.” He spoke excellent English, but with a hint of a Belgian accent. Despite being Covington’s bishop only a short time, he was already regarded as a beloved figure to not only the Catholic community but to the people of Covington in general. They found the new prelate to be modest and unassuming.

The old St. Mary’s Cathedral with the Bishop’s residence at left, where the little girl presented him with the silver dollar and “asked him to take it and build a new cathedral in Covington.” Courtesy of Paul A. Tenkotte.

A newspaper account described him as a man who exhibited a “kindliness of heart and charm that attracted more than passing attention.” In only a short time, he became “a friend and endearing figure to all, especially to children, of whom he was very fond.”

According to an 1897 Kentucky Post account of the meeting, the little girl then extracted a bright, new silver dollar from her dress pocket and “asked him to take it and build a new cathedral in Covington.” Maes listened to her as she “told him it was the first money that she had ever earned, and she wanted to help build a church with it.”

After asking her name and address, the Bishop took the silver dollar and the little girl went away happy.

That might have been the end of the story, except that Bishop Maes never forgot the encounter and remained deeply touched by the little girl’s gesture. It was a story he often recounted to friends in later years, perhaps to explain why he came to love the people of Covington so much.

A Morgan silver dollar identical to the one the little girl gave the Bishop. It became the first dollar that was contributed for the building of the new St. Mary’s Cathedral. Provided.

Upon his arrival as Bishop-elect in 1884, the community greeted him with “genuine enthusiastic admiration and affection.” But Camillus Maes was also a man of unquenchable faith who believed that God often spoke to man through the innocence of children. According to the story, he took the little girl’s gesture as a sign from God confirming that a new Cathedral will be built.

“From that hour,” wrote the Post, “Bishop Maes determined to act upon the suggestion of the child, and from that day he has labored without rest to accomplish the task the child had given him to do.”

The little girl’s gift became the first dollar contributed for the construction of the new St. Mary’s Cathedral. But it would be several years before the bishop would see any significant funds. He encouraged congregations for subscriptions and donations, recording the amounts from priests and religious, parishioners, even school children. But it wasn’t enough.

Estimates placed construction costs at roughly $150,000, an astronomical sum at the time. Then in 1890, wealthy Covington distiller James Walsh died and left Bishop Maes “$25,000 for a new St. Mary’s Cathedral.”

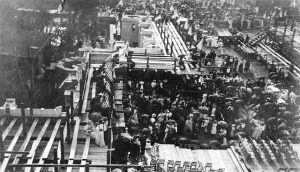

The ceremony of the dedication of the cornerstone, September 8, 1895. Courtesy of the Diocese of Covington.

Two years later, his son, James N. Walsh, along with distillery partner Peter O’Shaughnessy, gifted him $100,000 more. With renewed confidence, Maes hired architect Leon Coquard of Detroit and had plans drawn up for the new Cathedral.

But bad times were just around the corner.

The 1880s had been a period of robust economic expansion. But in February 1893, the economy crashed in what became known as the Panic of 1893. Despite the misfortune and the vast segment of the population thrown out of work, Bishop Maes pushed forward with his plans, and on April 13, 1894, he turned over the first shovel of dirt in a groundbreaking ceremony at the corner of Twelfth and Madison Streets.

It was a move that kept workers and tradesmen employed amid a crippling depression for the next seven years. By the following summer, the foundation had been completed and the walls were up to the bottom of the windows, sufficient enough progress to ceremoniously lay the new cathedral’s cornerstone.

Never in the history of Covington had such a religious demonstration been witnessed as there was on September 8, 1895, the Feast of the Nativity of the Virgin Mary. “It is calculated that Covington entertained more than 20,000 visitors yesterday,” the Kentucky Post reported. “The excursion trains from every direction were loaded to their utmost and the streetcars and bridges were crowded for hours…”. The parade stretched for four miles with 4,500 marchers led by Covington Grand Marshall, Judge W. T. Shine. “Minute after minute the crowd swelled,” reported the Cincinnati Enquirer, “until at 3:30 p.m., when the van of the big parade arrived.”

An assemblage of more than 60 church officials processed through the crowd and mounted the wooden steps of the temporary grandstand. Present was Archbishop William Henry Elder of Cincinnati, Archbishop John L. Foley of Detroit, accompanied by 59 priests. As they took their seats, the Enquirer reported “a little golden-haired girl, dressed in pure white, and reflecting from her face religious faith and innocence, clung to the cornerstone and hung there during the ceremonies.”

The cornerstone as it appears today. (Photo by Stephen Enzweiler.)

Bishop Maes noticed her too, and it would have been in his nature to take it as another sign – from another child – that despite the bad economic times, God was pleased with the work and all would be well.

Master of ceremonies, the Rev. John Gorey, began the ceremony with the blessing of the cornerstone and blessing of the walls. The entire assembly of the clergy knelt facing east toward a large wooden cross and chanted the Litany of the Saints, led by Bishop Maes. At its conclusion, Maes rose and moved toward the base of a stone column into which the cornerstone had been placed. In its top, a space had been hollowed out to accommodate a brass box. In the box were placed coins from the United States and Europe, blessed objects and medals, relics of the Holy Land, newspapers of the day, and a parchment with the account of the ceremony. Also in the box was a small, velvet case containing the silver dollar bestowed upon the bishop by the little girl years before. Maes placed the brass box in the hollow of the stone and mortared it in place with a silver trowel. A photographer positioned atop the north wall pointed his camera and snapped a picture of the scene.

By the time the cornerstone was laid, nearly a decade had passed since the little girl visited the bishop at his residence. Then a young woman, it is unknown whether or not she was present at the ceremony that day.

She had asked the Bishop that her name be kept a secret, and so her identity remains a mystery to this day. But the silver dollar she gave him still rests inside the brass box within the cornerstone, and people can still visit it today. Although the little girl’s identity may never be known, the magnificent Cathedral of stone and marble and glass will continue to live on in Covington’s memory as a monument to a child’s generosity.

Stephen Enzweiler is a writer, Cathedral Historian, and a docent at Covington’s Cathedral Basilica of the Assumption.

What hath one child wrought? Thanks, Steve, for this little known story.