By Capt. Don Sanders

Special to NKyTribune

“I killed a couple roustabouts,” the old pilot began with no prompting.

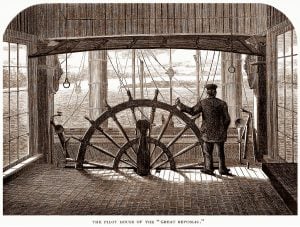

The pilothouse, otherwise hushed except for an occasional vibration caused whenever the steamboat found shallow water and labored, abruptly became a confessional for the elderly boatman behind the “sticks” guiding the vessel on the dark and trackless stretch of the Lower Mississippi River. Perhaps there was something the helmsman saw or imagined seeing in the gloom invisible to the younger man seated behind him on the high “Lazy Bench” that prompted the sudden admission to a series of crimes that occurred several decades earlier.

Back in the days when steamboats pushed wooden barges, they called,” the pilot continued, “a large open area directly in front of the boat with no barges a ‘duck pond.'”

Startled at his elder’s sudden remarks, the young man, the mate on watch in the pilothouse, could only muster:

“What’s that – you did what?”

“I killed two roustabouts, here on the river, when I was no older than you are now.”

The sweltering southern night would have proved stifling without a breeze blowing through the open window in front of the steersman and wafting out the doors on each side of the room. Besides, the mosquitoes were worse than the heat. The greenish glow from the radar screen and the minimal illumination emanating from the gauges and dials on the console made the elder riverman appear like a spectral messenger about to deliver a missive from beyond the reality of time and place.

“Back in the days when steamboats pushed wooden barges, they called,” the pilot continued, “a large open area directly in front of the boat with no barges a ‘duck pond.’ Most steamboaters believed the duck pond relieved pressures built up underneath the barges and increased the overall speed of the tow. Though the top of the pond looked smoother n’ glass, just beneath the surface the river churned and boiled. Anyone fallin’ into the duck pond was a goner… for sure.”

“What did you do,” asked the mate, “throw a man into the pond?”

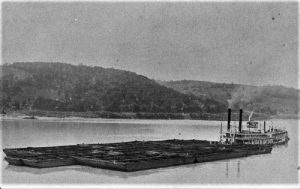

A Steam Towboat shoving a tow of wooden barges.

“Nah… nothing like that. We were tightenin’ ratchets on the starboard string, and when I told a shiftless SOB to tighten down on them wires better, he pulls out a knife and came after me.”

“Oh, hell,” replied the surprised young officer. “Then what happened?’

“I took off runnin’… had no choice… ran ‘round the duck pond to’ards the towboat, but that bastard stayed hard on my heels. Once I got on the head a’ the boat I had nowhere else ta’ go but back out on the tow. I made two whole laps ‘round the pond and was slowin’ down. No way could I last another. So when I made it back to the head of the boat the final time, I grabbed the fire ax off the bulkhead… and as he was atop me just as I swung it and split his head wide open – like smashin’ a melon. Killed him dead…”

“Jeeze… did anyone see you?”

“Of course,” answered the pilot, “half the crew witnessed it, and that was good. I stood trial, and some that were watchin’ testified in my behalf and I got off for ‘self-defense.’”

“You said you killed two rousters. What about the other?”

The old steamboatman didn’t respond immediately but stared straight into the darkness shrouding the river ahead as though he was not yet ready to unveil the circumstances of the second incident. The mate said no more and sat quietly on the Lazy Bench while the old man recollected the facts of the circumstances he was readying for confession.

“I knew the river as good as anyone in the pilothouse,” the old pilot finally began again.

“I was still down on-deck as the mate, but I knew the river as good as anyone in the pilothouse,” the old pilot finally began again.

“There was one roustabout deckhand – a real agitatin’ troublemaker – he challenged everything I said and done. Word comes back about the things he was stirrin’ up amongst the crew. It got to be either him or me. The boat wasn’t big enough for both of us.”

Perhaps the older man wanted to keep his words close within the enclosure of the wheelhouse, but since continuing his tale, his voice became softer and quieter until the young mate slipped off the Lazy Bench and sat nearer to where he could catch every word the elder man was saying.

“We carried a coal flat, or tender, on the hip alongside the steam towboat. At least once a watch, we’d get down inside the little barge and ‘passed’ coal up and into the bunker so’s the firemen had fuel to fire the boilers.”

“Passed?” asked the mate. “Did you throw the coal?”

“We carried a coal flat, or tender, on the hip alongside the steam towboat. At least once a watch, we’d get down inside the little barge and ‘passed’ coal up and into the bunker so’s the firemen had fuel to fire the boilers.”

“Hell, boy, we hauled it up in wheelbarrels across a wooden plank set ‘tween the boat and the tender. There weren’t any lights neither, except for the glow of the furnace ‘neath the boilers. What we did to see better, was take some flour from the cookhouse and spread a line of it down the length of the middle of the plank. That way, the light from the fires reflected off the flour trail, and that’s all the light the men wheelin’ the coal had.”

“So, where was the troublemaker all that time,” questioned the mate as he imagined the fuel passers wheeling their heavy loads of coal, up and across, from the flat to the steamboat.

The old pilot paused to make a radio call to a downbound towboat ahead:

“I’ll see ya’ on the one,” he informed the man in the wheelhouse of the other boat.

“Oh, he was there grumbling an’ carryin’ on and givin’ me a fit,” the pilot continued. “I’d noticed when the steamboat steered hard to starboard, a space of mostly three-to-four-feet-wide opened ‘tween the boat an’ the coal flat as the two steered away from one another. Though the old Mississippi was blacker n’ the coal inside the tender, I knew exactly where we were, an’ where we were headin’.”

“There weren’t any lights neither, except for the glow of the furnace ‘neath the boilers.”

As he listened, the mate imagined that even as a much younger man, the old pilot likely knew every inch of the Mississippi from New Orleans to Cairo better than he understood the layout of the road where he lived when he was off the river. So when the elder boatman said he knew “exactly where he was,” every word was as good as the gospel.

“Understand now, I was a’standin’ down inside that tender next to the plank where them rousters were wheelin’ the coal across to the steamboat. I knew that a bend was comin’ up soon, and the pilot, up-top, would be steering the boat hard over to starboard. And I saw my chance, once and for all, to get rid of that agitatin’ troublemaker.”

“What did you have in mind?”

“I had to time everything z’actly right. So when I see it was that feller’s turn to shove a wheelbarrel load a’ coal across to the boat, I waited just before he got onto the plank. Then I slipped a small lump of coal under one side of the board on the deck of the steamboat right as the pilot was fixin’ to turn into the bend.”

The young mate, seated at the elder pilot’s side, saw what was about to transpire in the darkness of that long-ago night, and though he wanted to say, or do, something to change the outcome, he knew it was too late, so he sat motionlessly and listened.

“In the light of the flames ‘neath the boilers, I saw the hatred in the eyes’ of the instigating rabble-rouser when his face passed close to mine as he wheeled his load across the plank. No sooner than he was past and onto the middle o’ the wooden board, the pilot ran the rudders hard to starboard and the steamboat steered away from the tender. A wide gulf opened between the boat an’ the tender with the river rushin’ through the gap. One more step, the plank flipped and that bastard, the wheelbarrel, an’ all the coal disappeared into the Mississippi River!”

Before the young mate could respond, the pilot turned his face toward him in the darkness. In his most mocking voice, the old man hissed with a burst of cold laughter that sent a chill throughout the sweltering pilothouse as he added:

“And they never did find that sonofabitch…Haw, Haw, Haw!”

Captain Don Sanders is a river man. He has been a riverboat captain with the Delta Queen Steamboat Company and with Rising Star Casino. He learned to fly an airplane before he learned to drive a “machine” and became a captain in the USAF. He is an adventurer, a historian, and a storyteller. Now, he is a columnist for the NKyTribune and will share his stories of growing up in Covington and his stories of the river. Hang on for the ride — the river never looked so good.

Click here to read all of Capt. Don Sanders’ stories of The River.

Stayed on the edge of my seat throughout this whole story! Wonderfully descriptive writing style that consistently places the reader in the middle of the action! Thoroughly enjoyed this!

My name is Jerry Kitte from Cincinnati, Ohio. I found an old journal from someone who worked on the Island Queen (?) or the wharf boat. The journal starts July 1946 & the last entry is 21 Nov. 1949. I would like to talk to ya about some of the entries. Please call 513-871-4012. Sure would like to talk “riverboatin'” with you. Thank you.