By Steve Preston

Special to NKyTribune

While loss of a loved one is always a tragic event, grieving survivors seemed to take things to the extreme throughout the course of the nineteenth century. The 1800s were a time of great technological advances, yet still filled with mystery and superstition in regard to death.

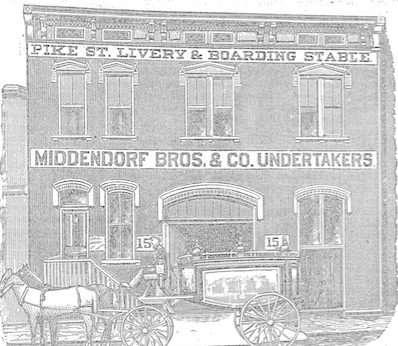

Middendorf Brothers and Co. Undertakers, Pike Street, Covington, Kentucky, 1880s. Like many early undertakers, the Middendorf brothers also operated a livery and boarding stable, where you could rent horses, carriages, and also stable your horses. Source: Leading Merchants and Manufacturers of Cincinnati and Environs (1886), p. 245.

One technological advance was the advent of photography. People now had the chance to have their picture taken and have a memento of a certain place and time. Due to the expense of early photography, “post-mortem” photos were often taken as a way to have a keepsake of their dearly departed. Families would pose with the deceased, who was propped up among the living. This was often done by parents who lost a child.

Another way of remembering the deceased was to make a keepsake from their hair. Watch fobs, jewelry, and wreaths made from hair were often kept as a reminder and memory of their loved one. The hair would be intricately woven into these forms. Heritage Village has several examples of this “Hair Art” in its collections.

Homes became a time capsule of the time of death. Clocks were stopped, windows shuttered and covered in black crepe, a black ribbon was placed on the front door so that the outside world would know before they knocked that the family was in mourning. Mirrors were covered so that, as superstition held, the deceased would not become trapped in them. Woe to the family that had a mirror fall and break at this time, as it would portend another tragedy for the bereaving family.

During the Victorian era, the family would all be dressed in black. It was started by England’s Queen Victoria, who wore black the rest of her life after the death of her husband, Phillip. Mourning clothing was actually marketed. Those too poor to afford them would often dye existing clothes black, then bleach them back later. Women would wear their mourning clothes for a prolonged period. There were rules to when and what a woman could wear while in mourning. For men, it was not as strict, nor as long. After women who were in mourning began to venture out, they often wore a veil to hide their eyes swollen from crying.

Post-mortem photo of a man propped up in a chair. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

A funeral was a true sign of what the living thought of the dead. Families tried to send their loved one to the afterlife with as much dignity, and pomp as possible. This could include hiring professional mourners or “mutes” to follow the procession to the burying ground. By the way, the casket was taken out of the home “head first” so the dead could not beckon the living to join them.

After the burial, the family’s stress and concern for the dead did not stop. Throughout the 1800s, many feared being accidentally buried alive. Some purchased elaborate coffins that allowed for possible notification to those above ground that the deceased was still very much alive. Bells could be attached above ground with a string running to the coffin so that they might be “saved by the bell.”

The study of anatomy and illness was not nearly as advanced as today. Cadavers were highly sought after by medical schools despite the reprehension of using the deceased for study. “Resurrection Men,” grave robbers, would often steal the recently departed at night and make good money delivering them to medical schools. Families who could afford it often hired someone to watch over the grave at night to make sure their loved one would not be disturbed. Working the “graveyard shift” is how some people made money.

Many of these mourning customs and rituals have faded into memory. Our understanding of the stages of the bereavement process has aided us in helping those grieving.

Superstitions have given way to a newer tradition of celebrating the lives, achievements, and love of our dearly departed.

Steve Preston is the Education Director and a Curator of History at Heritage Village Museum. He received his MA in Public History from Northern Kentucky University.