By Steve Preston

Special to NKyTribune

In the spring of 1786, Major Benjamin Stites of Redstone, Old Fort, Pennsylvania was on a trading trip down the Ohio River with a flatboat full of flour, whiskey, and other popular goods for Limestone (Maysville), Kentucky.

He found trading competitive in the river town, as many traders stopped there. He decided to go further inland to Washington, Kentucky.

While there, a Shawnee raiding party swept through the area, stealing horses before quickly crossing the Ohio River back into Ohio Country and to their village. An experienced Indian fighter, Stites joined the local men in pursuing the warriors. The Kentuckians and the trader made their way into the Ohio Country. They pursued the Shawnee as far as present-day Xenia, Ohio. Knowing they were deep in “Indian Country” and outnumbered, they headed back leisurely through the Miami Valley.

Stites fell in love with the land between the Miamis and resolved to start a settlement there.

Upon his return back east, Stites went to New Jersey and sought out Judge John Cleves Symmes. The Judge and his investment partners were looking to invest in land speculation in the Ohio Valley. Stites told him of the land he had seen between the Little Miami and Great Miami Rivers. Symmes was a member of Congress and had influential friends. Based on Stites’s report, Symmes and his partners were instantly interested. With Symmes’s influence, connections, and wealthy friends, only one thing stood in the way of obtaining the land, the Native Americans who claimed it as their own.

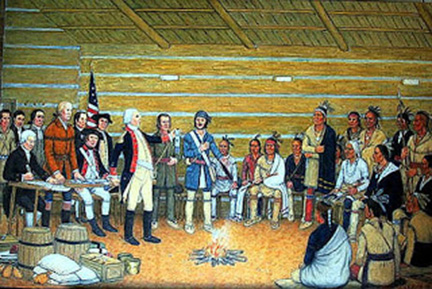

Treaty of Fort Finney. (Source: Great Warriors Path)

At the end of the American Revolution, the United States gained control of the lands west of the Appalachian Mountains, and the native peoples who lived on them, from the British. The young American government firmly believed that they had acquired this new land through their defeat of the British during the war. However, while most Native American tribes sided with the British, they were not involved in the peace process and never considered themselves defeated.

A series of treaties going back to when England controlled the colonies had ceded the Ohio Valley lands to the European settlers without the participation of the tribes who actually lived here. As a result, the tribes living in Ohio Country rejected these early treaties. In hopes of maintaining the fragile peace, the Federal Government decided to renegotiate with those tribes. The government was not interested in a true negotiated peace, however. Rather, they intended to impose a treaty. The country needed money after the Revolution and intended to make it by selling land.

The fledgling American government, maintaining that they had acquired this new land by “right of conquest,” chose to negotiate the treaty for Southwest Ohio as conquerors. To emphasize this point, they sent the most feared and hated man by the tribes as a negotiator, George Rogers Clark. The “Hero of Vincennes,” as he was known, had spent the latter half of the Revolution raiding Indian villages in present-day Ohio. Clark believed that only the threat of violence would motivate the Ohio tribes to seek peace.

In October 1785, Fort Finney was built by United States troops near the mouth of the Great Miami River. Today, the site is the coal yard of the Miami Fort Power Plant. This was to be the meeting place for talks with the Shawnee, Delaware, and Wyandots to make peace and allow white settlement of Southwestern Ohio. Both the Delaware and Wyandots were early arrivals. The Shawnee, however, were reluctant to attend. The Shawnee were not happy with proposed settlements north of the Ohio River.

Marginalized by other tribes and not a participant in previous treaties, they were desperate to hold onto the land.

Emissaries of the government were sent out to find the missing Shawnee and to warn them that this was their only chance to negotiate. Concerned again that another treaty would be signed without them, they reluctantly agreed to attend the talks. By the time the Shawnee arrived, it was January 14, 1786. Of all the Shawnees in Ohio, only roughly one-third chose to attend and only one head chief, Moluntha, was in attendance. He was escorted by his two war chiefs, Captain Johnny (Kekewelpalethy) and Aweecony. The attitude of the Shawnee warriors accompanying the group was, understandably, barely contained hatred for the whites.

Samuel Parsons, a future Cincinnati judge, Richard Butler and the much-feared George Rogers Clark were treaty representatives for the United States. After ceremonial pleasantries were exchanged, the Shawnee joined the Delaware and Wyandots at the council for talks. The proceedings were tense from the start.

General Richard Butler of the American envoy informed the assembled Indians that since they had fought alongside the British, they too were defeated. The British had ceded the land and to avoid punishment, they must remain peaceful and accept whatever offer of land the Americans allowed them to keep. The Shawnee were also to leave several of their own as hostages to prove good faith in returning white captives taken during the war. The session ended with the obviously infuriated Indians exiting the council house for the day.

When treaty negotiations resumed the following day, it was the Shawnees’ turn to speak. Captain Johnny, one of the two war chiefs, rose to speak. He told the American envoy that the Shawnee did not understand “…measuring out the lands.” It was given to the Shawnee by the great spirit, Waashaa Monetoo. Captain Johnny told them they desired peace and would return any captives, but that the land north of the Ohio River was not for white settlement. As he finished, he presented the Americans with a wampum belt that was half black for war and half white for peace. According to Ebeneezer Denny’s military journal, after Captain Johnny placed the belt on the commissioners’ table, “None touched the belt-it was laid on the table; General Clark, with his cane, pushed it off and set his foot on it. Indians very sullen.”

Briefly taken aback by the Shawnee belligerence, the commissioners responded in no uncertain terms. Richard Butler was the one to speak and he said: “We plainly tell you that this country belongs to the United States…” He went on to tell them they should be thankful for their forgiveness and they had two days to decide whether to accept the treaty, but after that, they would feel the might of the United States. The commissioners then adjourned the proceedings for the day. The Shawnee exited the council house with tensions running high.

Later the same afternoon, Moluntha requested and was granted another meeting. This time, with Moluntha speaking, the tone was much more conciliatory. Forced into a corner with threats of open war against their villages, Moluntha and other Shawnee chiefs in attendance agreed to sign the treaty. They did so much to the ire of many of their warriors, who left the proceeding early in disgust.

On January 31, 1786, it was official. The Shawnee had surrendered the southeastern part of their homelands, in present-day Ohio and Indiana, to the United States. All the Native American delegations left with supplies for the journey back to their villages and gifts awarded for signing. As expected, the remaining two-thirds of the Shawnee tribe rejected the treaty. They stated that one small faction was not authorized to sell their land on behalf of the whole tribe.

Because of the belligerent attitude of the United States in their quest for land, their attempt at peace brought war. Land speculators, such as John Cleves Symmes, saw the land dispute as settled. They came and started communities on the land that the tribes were still ready to fight for. This led to a protracted war that was disastrous for settlers and Indians alike. One of the first casualties was Moluntha.

In October of the same year he signed the treaty, Moluntha’s village, well above the treaty line, was attacked by Kentuckians seeking revenge for defeat at the Battle of Blue Licks. During what became known as “Logan’s Raid,” Moluntha had raised the American flag on his lodge and was taken captive with his copy of the Fort Finney treaty in his hands. A Kentucky hothead by the name of Hugh McGary misunderstood the chief’s answer when he asked if he was at Blue Licks. Thinking that Moluntha had answered in the affirmative, he buried his tomahawk in the elderly chief’s head and scalped him. In retaliation, the Ohio Valley would see all-out war until 1794.

Steve Preston is the Education Director and a Curator of History at Heritage Village Museum. He received his MA in Public History from Northern Kentucky University.