By Stephen Enzweiler

Special to NKyTribune

When Cincinnati artist Marlene Steele pulled into Fort Mitchell’s Highland Cemetery on Memorial Day 2011 to attend a veterans’ commemoration service, she hoped to take time afterward to visit the grave of her childhood art teacher, Aileen F. McCarthy.

Steele, today one of the Cincinnati area’s most prominent artists and painters, credits McCarthy with inspiring her as a young girl to follow her dream and make art her life’s work.

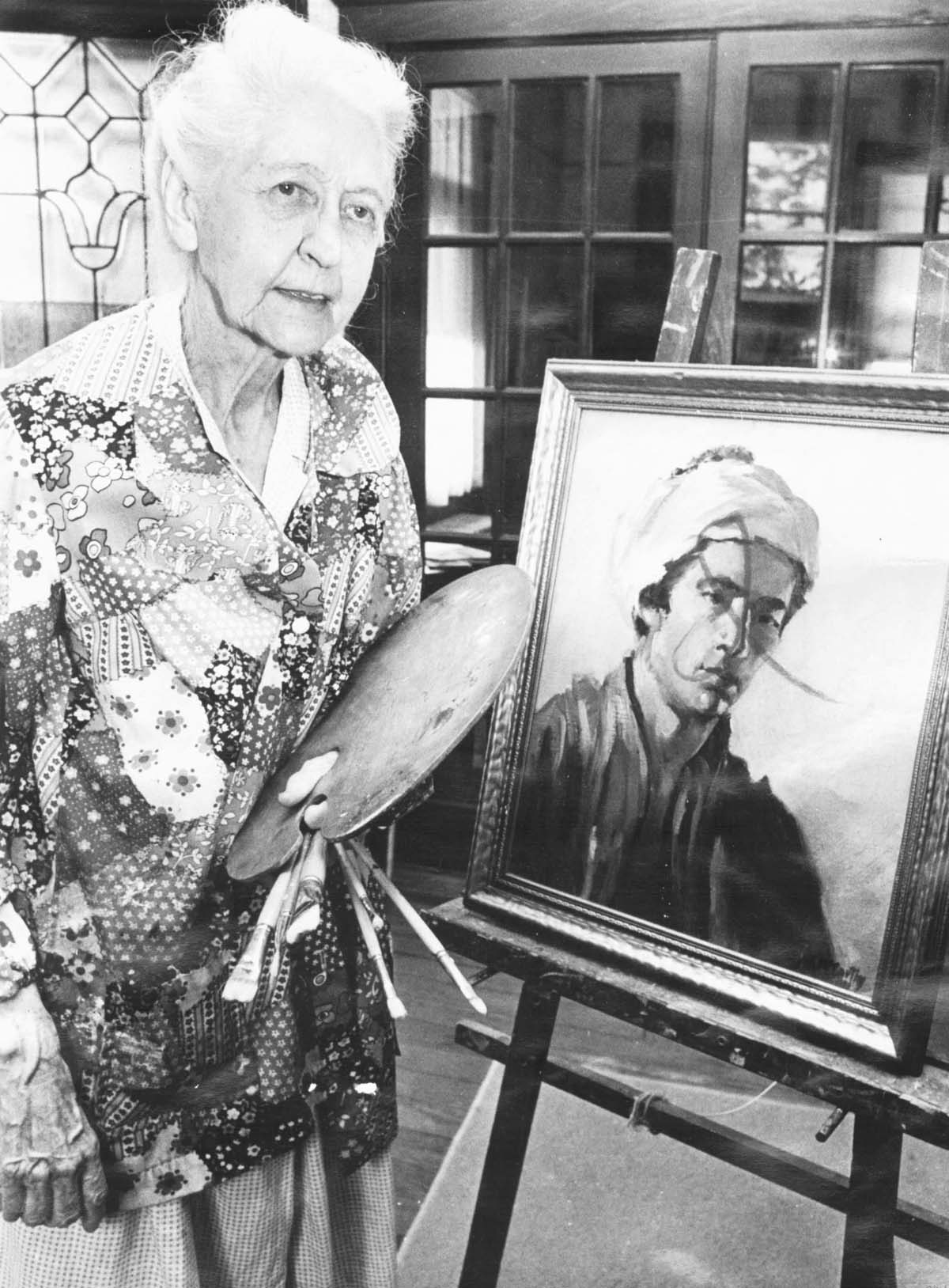

Aileen McCarthy was the last living student of artist Frank Duveneck. She died on Saturday, January 23, 1982, at age 95. Courtesy of the Kenton County Public Library

“I went to this memorial service,” Steele recalled in her art studio earlier this year, “and I thought I’d remember where it is.”

She drove through the oak-bemused avenues and walked the shaded groves of the cemetery grounds, but she was unable to find it.

A week later, she returned to Highland and inquired at the cemetery office. They quickly found McCarthy’s grave in the records and pointed to its location on a map. But even with a map in hand, Steele stood on the grassy slope at the spot to which she was directed and still found no grave. As it turned out, a headstone had never been provided to mark McCarthy’s final resting place.

“I felt ashamed,” Steele confessed. “It was my thought, that given what she had given to me, she did not have a stone. Not even a marker. Nothing.”

Marlene Steele was one of many area students who spent years of Saturdays in their youth climbing up the front steps of McCarthy’s home on West 21st Street in Covington to be taught art.

“I studied with her in the sixties,” Steele said, remembering there was always the “immediate whiff of oil paint as soon as you walked in the door.”

The house was usually bustling with students, some of whom came to take piano lessons in the parlor from the artist’s niece, Helen Riley. Others were McCarthy’s art students, who collected upstairs in the single front room she converted into her art studio. There, they were taught drawing, pastels, water color, pen and ink, and oil painting. Her teaching methodology was always to mix everyone together, whether beginners or advanced, and she keenly instructed students according to their interests and abilities.

Artist Frank Duveneck (center), surrounded by students in one of his painting classes (ca. 1890-93). Some of the women students can be seen wearing smocks and holding palettes and brushes. Courtesy of the Kenton County Public Library.

Born on September 18, 1886, Aileen F. McCarthy was the third daughter of Jeremiah and Cordelia Lambert McCarthy of Covington. She developed an interest in drawing as a child and studied under Sister Josina Whitehead while a student at LaSalette Academy. After graduating from LaSalette in 1905, she went on to study at the Cincinnati Art Academy. There, her talents won her scholarships, and she studied under sculptor Clement J. Barnhorn, artist George Elmer Browne and landscape artist Emile Gruppe of Gloucester, Mass. But it was renowned artist Frank Duveneck under whom she really wanted to study.

Duveneck had always been accepting of female students in his oil painting classes, a concession in an era when art schools and academies were still trying to determine the role women played in the late 19th century art world. Figure and portrait painting in oils had always been considered the domain of men, but Duveneck readily accepted women with demonstrated ability into his figure and portrait classes. In 1905, 19-year old Cincinnati Art Academy student Aileen McCarthy found herself accepted into such a class with the famed painter.

“She struggled very hard,” said Steele. “I remember conversations with her. She knew what she had won when she was accepted in his class, and it was not a thing easily accomplished.”

The former Aileen McCarthy House on W. 21st Street, where the artist taught generations of young Northern Kentucky art students. Classes were held in her studio on the second floor (right front window). Photo by Patricia Enzweiler.

After Duveneck’s death in 1919, McCarthy grew her career, gradually emerging as one of the pre-eminent teaching artists in Northern Kentucky. She taught at LaSalette, then turned to her own career of painting portraits and teaching in her upstairs studio. She never married, but remained active in the community for the rest of her life. By the late 1970’s, when she could no longer live on her own, she moved into St. Charles Care Center. Even with failing eyesight, she was known at St. Charles for the many sketches she drew as long as she could see well enough to move the pencil around the page. She died there on January 23, 1982 at age 95.

There are no records to indicate why her grave at Highland Cemetery remained unmarked for more than three decades. Steele turned to a friend of hers, Bernie Schmidt, to gain a perspective on what might be done about it. Schmidt had also been a student of Aileen McCarthy and was then chair of the Department of Art at Xavier University.

During many visits and collaborative discussions, the subject of their former teacher would surface and the conversation invariably drifted to their respective memories of Aileen. One evening over pasta at Pompilio’s restaurant in Newport, Steele brought some sketches for a headstone and the project finally took root.

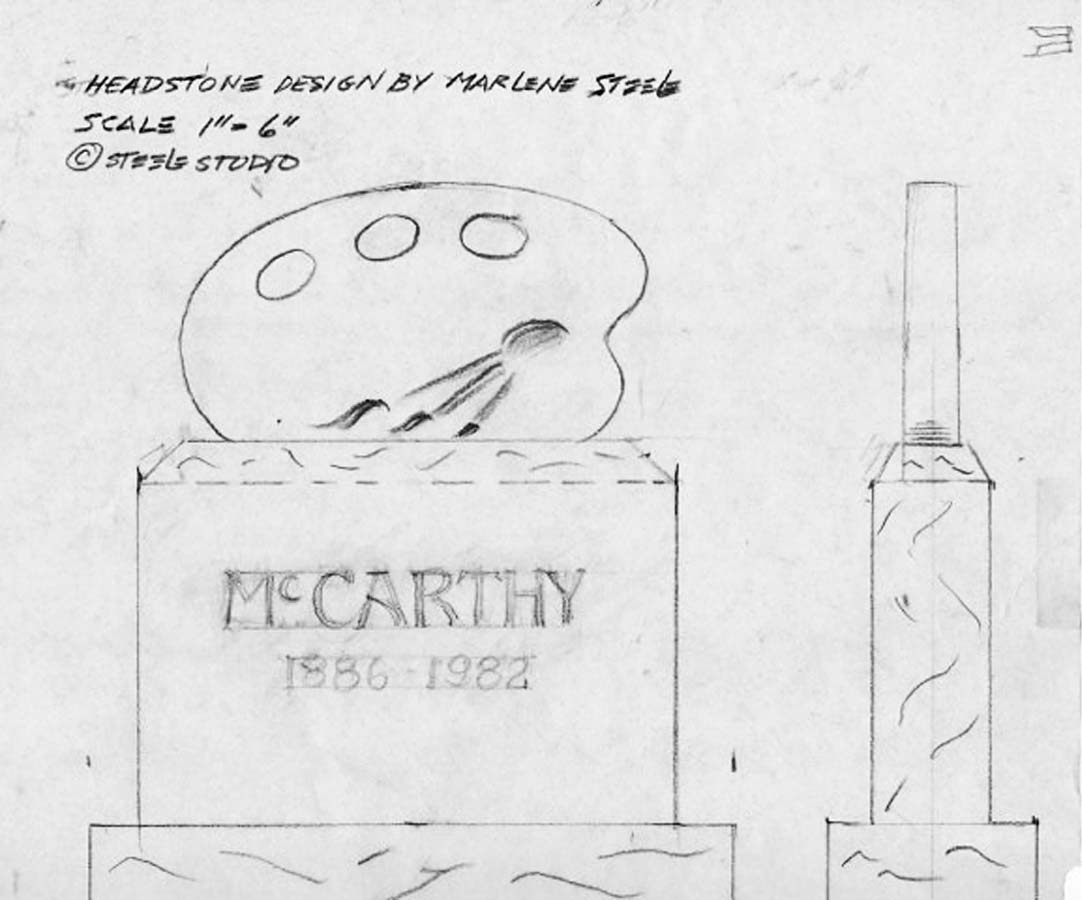

“We were sitting there and I had thought of this enough to make a sketch of what I thought the stone should look like,” Steele explained. “I had two sketches. One was a palette-like shape at the top, but it morphed into a taller monument.”

Schmidt liked the idea immediately and offered to cover the cost of the stone’s foundation. Schmidt encouraged the next step: to investigate the specific cemetery regulations about what kind of headstones could be placed on graves. For the next year, the idea fell to the back burner.

“I wanted to do it, but other stuff came up,” Steele said. But October 25, 2013 was a wakeup call when Bernie Schmidt died after an illness, leaving Steele with a decision to make. “Bernie’s death brought it home for me,” she reasoned. “I said to myself – if I’m going to do this, I need to do it NOW.”

One of the original designs conceived by Steele for the headstone. Courtesy of Marlene Steele.

Her first move was to walk the gravesite with the cemetery’s general manager, Thomas Honebrink. Honebrink wasn’t aware of who Aileen McCarthy had been. Steele explained her impact on the Northern Kentucky arts community, as well as her association with Frank Duveneck. The cemetery manager suggested that the best headstone design would be one that was both appropriate to McCarthy’s unique status and yet would also fit in with the surrounding cemetery monuments. Steele’s sketches already seemed to fit the bill.

The lower part of the monument would be an ordinary granite headstone. Mounted on top would be a limestone sculpture in the shape of an artist’s palette. Three holes carved through the stone would represent the three primary colors of the artists craft – red, yellow and blue. Steele explained that this was done so that at any season of the year, anyone could go and see the world through her palette. Below the three holes would be three different lengths of brushes carved in relief. These symbolized the three different mediums McCarthy primarily taught, which were oils, pastel and watercolor.

She showed her sketches to Katherine Meyer, a professor friend at Northern Kentucky University. Meyer suggested approaching Kentucky arts organizations for financial assistance. One organization recommended using Kentucky sculptors as a condition of patronage; but after examining various artists, none seemed able to deliver the kind of memorial appropriate to McCarthy’s stature. As time went on, the process of seeking financial backing began to grind away at the spirit of the project. Finally, Steele opted to simply manage it herself.

Now working without constraints and able to pursue a truly creative end to the project, the sculptor she felt was best for the job was Cincinnati sculptor Karen Heyl, a longtime friend. Heyl liked the sketches and the mission of the project. She drew the design for the top sculpture on a limestone block and went to work. (Heyl generously donated the carved Indiana limestone out of respect to Aileen McCarthy’s memory.) Karen’s artistic talent and technical experience insured the success of the Indiana limestone/granite structure.

At the dedication of Aileen McCarthy’s headstone on September 19, 2015 are (L to R) Setsuko LeCroix, Charie (Charlotte) Fischer, Patricia Pranger, Katherine Meyer, Lawrence Busse and Marlene Steele. Fischer, Pranger, Busse and Steele are all former students of Miss McCarthy. Photo by Stephen Enzweiler.

By the summer of 2015, Heyl finished carving the palette and delivered it to the monument company for mounting atop the granite base, which would bear McCarthy’s name and dates of birth and death. A week before the dedication, Steele visited the grave to see how it looked. But, she discovered that the stone had been installed incorrectly as a footstone, not as a headstone as was intended. Within the week, the mistake was corrected.

On the cool, overcast afternoon of September 19, 2015, a small group of McCarthy’s former students, along with project supporters, gathered at the graveside. It had been 33 years since her passing…33 years of silence, of anonymity beneath the oak trees, 33 years without any way to know she was even there. But on this day, all that changed. The group gathered around, and Steele formally unveiled the finished headstone and sculpture. In her remarks, she noted that McCarthy had given up much to dedicate her life to her craft.

“Miss McCarthy was an artist dedicated to her career from her early years,” she said. “She followed the prescribed rigor for the dedicated female student. She studied with the great ones of her day: Frank Duveneck, Clement Barnhorn, Emile Gruppe. She lived her life alone with her work, eschewing the duties to husband and family. She opened her studio to her students. Her unselfish contributions to the art community as a teaching artist has been an inspiration in my life. She was a conduit of the great principles of art from Duveneck’s generation to our own times.”

Today, for visitors who pull into Highland Cemetery and drive down the oak-bemused lanes that curve and dip through the quiet landscape, there is a spot atop a small grassy slope where a new presence may be found, where there is silence no longer, where one may now easily find a monument that marks the final resting place of Aileen McCarthy, Frank Duveneck’s last living student and one of Covington’s most iconic artistic legends.

Stephen Enzweiler is a writer and journalist. He has been a columnist for the Kentucky Enquirer, the Oxford Citizen, and was a senior editor at Y’all Magazine. He is the author of “Oxford in the Civil War: Battle for a Vanquished Land.”

very nice article and very nice of Marlene Steele!!!

Enjoyed this very interesting and informative article, but find myself interested in the author’s use of the word ‘bemused’. Twice he uses the phrase “oak-bemused”lane and I found myself wondering how the oak trees lining the pathway could be confused or dazed?? Now I am slightly bemused and curious!

Define bemused: marked by confusion or bewilderment : dazed; lost in thought or reverie — bemused in a sentence.