By Melissa Patrick

Kentucky Health News

A recent survey found that one in 12 of Kentucky’s high-school sophomores said they had attempted suicide, prompting experts on the topic to discuss what is being done about it. The main solution offered was more family support for teenagers, even those who may be only temporarily troubled.

In a tone of incredulity, Dr. Allen Brenzel, medical director of the state Department of Behavioral Health, Development and Intellectual Disabilities, told the legislature’s joint health committee Nov. 15, “Almost 7,000 students in this survey said on a piece of paper that they actually attempted suicide within the previous 12 months.”

Brenzel, the last speaker on the topic, noted that there has been an upward trend in teen suicide deaths, both nationally and in Kentucky — where the total suicides among teenagers more than doubled between 2014 and 2016, jumping from 19 to 44.

“From 2014 to 2015 we saw an almost doubling in the adolescent suicide completion rate,” Brenzel said. “This is very disturbing, very concerning. It led us to re-double our efforts to collect and partner with many agencies to determine what is the nature of this increase, why are we seeing it , what’s happening with our youth and what can we do around prevention.”

The 2016 Kentucky Incentives for Prevention survey, given at participating Kentucky schools to even-numbered grades from 6 to 12, found that 15.4 percent of Kentucky sophomores said they had “seriously considered” attempting suicide in the 12 months prior to the survey. The national average is 18.3 percent.

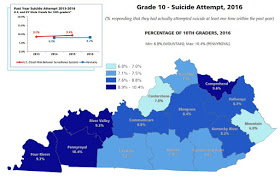

The suicide-consideration rate ranged from 12.2 percent in Eastern Kentucky to 18.2 percent in the Communicare mental-health region (the Lincoln Trail Area Development District) and 17.6 percent in the Pennyroyal region (the Pennyrile Area Development District).

“We’re not exactly sure we understand why, but we know there is heavy military family presence in those areas, and we do have some concerns about the cumulative effect of multiple deployments, which is a stressor in military families,” Brenzel said. He added that the state has allocated extra money toward suicide prevention efforts in those regions to help military families, and such targeting has been proven to work. Fort Campbell, the Army post with the most deployments, is in the Pennyrile district; Fort Knox is in the Lincoln Trail district.

The Pennyroyal and the other two Western Kentucky regions (and the Comprehend/Buffalo Trace region in northeastern Kentucky) had the highest percentages of sophomores saying they had attempted suicide. Statewide, 12.5 percent of 10th graders said they had made a plan about how to attempt suicide, which is called suicidal ideation; 8.2 percent, or one in 12, said they had actually attempted suicide in the previous year.

“A significant number who have ideation progress to an actual attempt,” Brenzel said, “so that is why identifying those students earlier and preventing that progression on that continuum is important.”

Dr. Hatim Omar, chief of the Division of Adolescent Medicine at the University of Kentucky, said it’s time to stop thinking about suicide as a mental-health issue and make it a public-health issue.

He said one-third of teen suicides have nothing to do with mental health, but are the result of a same-day crisis, and that with the proper prevention efforts and supports — and a lack of access to a lethal method — these suicides are often preventable.

For example, he said parents shouldn’t just dismiss a teen’s broken heart or concerns about a failing grade, but take time to commiserate with the child and not simply brush off such events as part of growing up.

“We want parents to wake up and pay attention to their kids, and listen to them and not ignore them,” he said. “But we fail in this very basic thing.”

Omar emphasized that research shows that a teen will “do fine if they have one adult who cares about them, if they have a safe place to interact with this adult ,and if we actually give them something useful to do. So why don’t we do that? It sounds really simple.”

He said the lack of adult support is illustrated by youth in his practice who tell him they no longer have family dinners, while 10 years ago they ate with their families about 15 times a month. He added that even when families eat together, it is often with their noses in a smartphone.

“That’s our biggest problem. We are losing our families,” Omar said “Kids are not feeling supported.”

Risk factors and prevention strategies

Risk factors for teen suicide include a prior attempt, substance abuse, being discharged from a mental hospital, having a firearm in the home, and a bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, Omar said. He added that “major depression” is only responsible for 2 percent to 4 percent of teen suicides.

Omar noted the importance of storing guns and bullets in different places. He told the story of a 16-year-old patient who had decided to kill himself: He found a gun in his house, but couldn’t find bullets, so he gave up after 30 minutes.

“That’s the difference between life and death,” Omar said.

All middle- and high-school students in Kentucky are required to receive some form of suicide-prevention education by Sept. 1, and teachers are required to receive at least two hours of self-guided training. The state has also implemented several peer-led “Sources of Strength” programs that promote resiliency and overall health, with plans to broaden this program to all school districts.

Some districts are doing even more to prevent teen suicide.

Lincoln, Boyle, Harrison, Nicholas and Scott counties use the “Stop Youth Suicide” program, which Omar founded in 2000. This program screens every student starting in sixth grade to determine their suicide risk and “most importantly” let them know help is available, Omar said.

Showing data from Lincoln County, Omar noted that when it started the program in 2007, the school district was seeing an average of two suicides per year, but since then there has only been one, last year. He added that the high school has seen higher attendance and graduation rates, and lower dropout and teen-pregnancy rates.

Dusty Phelps, a psychologist in Pulaski County, said its suicide-prevention and mental-health program, called “Kentucky Aware,” is a grant-funded pilot program that could become a statewide model.

Among other things, the program integrates school-based mental-health services into the education system; teaches staff how to recognize signs of trauma and how to respond; creates partnerships with mental-health agencies to support students; and teaches students how to be active participants in their own mental-health care.

Lori Price, a psychologist and coordinator of student and family support Services in Pulaski County, said the district has nurses in every school who are “very tied” to the district’s family resource and youth service centers.

“We have trained our nurses in youth mental-health first aid and intervention. And many times our youth service centers and our nurses are the ones that recognize what is going on with our youth,” she said. “Our family resource centers and our nurses are a very strong component to our mental health services in our school district.”

Price said parents need to be aware that there is a “very dark world on social media,” which offers suicide as an option.

Sen. David Givens, R-Greensburg, and Rep. Robert Benvenuti, R-Lexington, both said social media promote the fallacy that everyone else has a perfect life and encourages a constant comparison that is not real.

“That is a burden for a young person with low self-esteem to have to carry,” Givens said. “So there has got to be a component of technology usage, digital literacy, understanding that these things lie.”

I have concerns after the event in Washington DC. What if a child is different than the majority of the students in his school. Is there inclusivity and acceptance, or mocking and bullying? Does a child need to hide his sexuality or race?